Friday 1st January 2021

Christian Leadership Formation programme launched for Sixth Form students

Stefan Kaminski

Government leaders are easy targets for our criticisms, however justified these may be. But we cannot escape the fact that leaders do not grow on trees. They emerge from our very own society, and their shortcomings to some extent reflect our own collective failures in educating and forming our young people.

As Catholics, we have a duty to provide a solid philosophical and theological formation for those whom we wish to see safeguarding and promoting a Christian society. We cannot expect future government ministers and legislators to formulate and implement ethically-coherent laws that distinguish between morally-licit surgery and invasive operations, genuine rights and the demands of lobbyists, if we have not given them the framework for such judgements.

The Lord Alton of Liverpool is one of many who have long recognised the need for a greater preparation of potential leaders. When he founded The Christian Heritage Centre charity, he dovetailed his desire for such a preparation with the charity’s objectives.

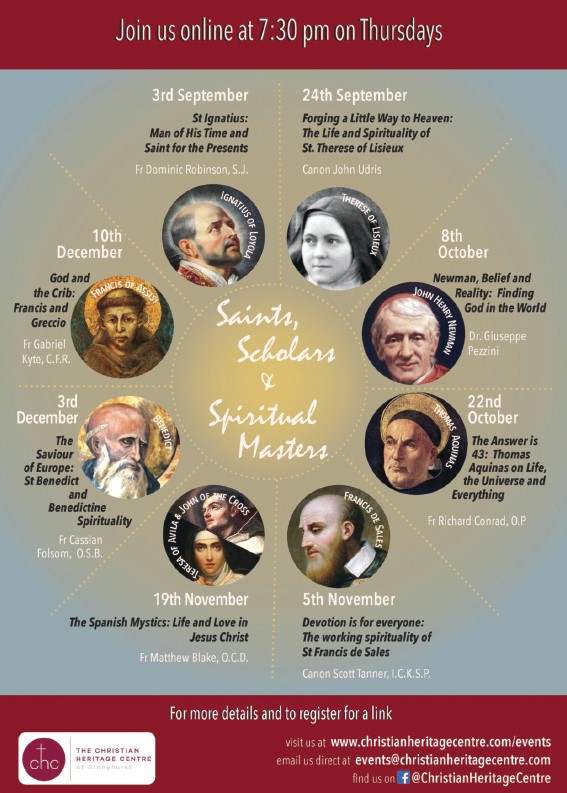

The Centre is delighted to now announce the launch of its first Christian Leadership Formation course. It has partnered with St Mary’s University, Twickenham and the Catholic Union of Great Britain to offer a course consisting of three, residential modules delivered over a nine-month period. Organisations such as Alliance Defending Freedom and Catholic Voices, besides other independent, Catholic academics, are also contributing to the course, so that participants will receive a variety of top-quality input from experts in different fields.

“In an increasingly fast moving and complex world where decision makers have to grapple with ethical challenges, about which they feel ill-equipped to deal with, a course which provides formation, maps and sign posts will be greatly welcomed by many,” noted Lord Alton.

Applications for the course are now being welcomed from Lower Sixth students until the end of March, when fifteen students will be selected on the basis of their personal statements, recommendations from their school, academic grades and personal references. The students who will be offered a place will be those who are motivated by their faith to help shape and create a society founded on Christian values; those who are driven towards public life by a love of God and of neighbour.

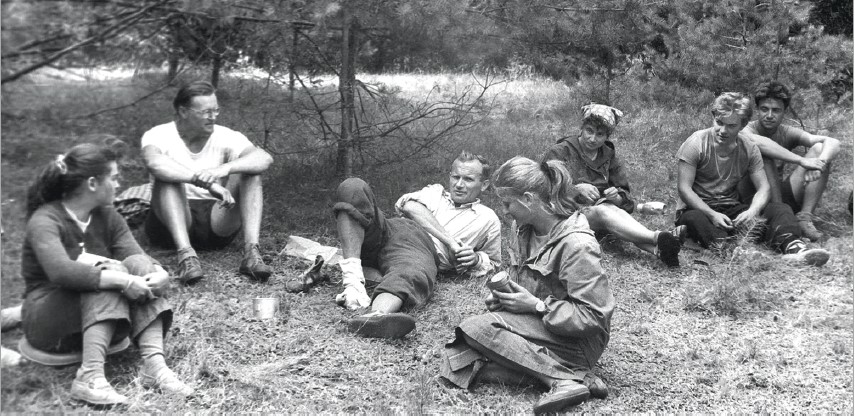

The successful applicants will gather at the charity’s Theodore House, in Lancashire, at the end of July for the first, five-day residential. Two shorter residentials will follow in London, during the October half-term and the Easter break of their last year of school

Each residential will have a particular focus. The first will consider the prerequisite “Philosophical Foundations for the Common Good”, providing the students with a grounding in concepts such as human dignity, natural law and conscience. The bedrock of Catholic ethics, these concepts today remain mostly in name whilst their origins have been lost from view and their meaning substantially mutated. The course will seek to offer students the necessary vision and tools to engage both faith and reason in pursuit of the truth that is common to all people, and which is the only source of a genuine and common good.

The second residential will offer input on “Human Life and Ethical Considerations”, covering a range of issues from the basic definition and understanding of human life, through stem cell research and end-of-life care. As St John Paul II noted, “A society will be judged on the basis of how it treats its weakest members; and amongst the most vulnerable are surely the unborn and the dying.” This second module will thus aim at instilling in our future leaders a profound sense of the full dignity of life at all its stages, and a clear, moral framework to tackle the continually-growing field of ethical issues around the existence and the nurture of human life.

The final module will focus on “Applied Political Leadership”. It will examine Catholic Social Teaching in the context of the current political field, providing students with a clear, applied understanding of the purpose and role of politics as well as the essential principles that are necessary for a pursuit of the common good. One particular field that will also be addressed, which so many are particularly sensitive to today, is that of the management of public finances. Economic interests are often at the heart of political divisions, and yet the Church has long-since elaborated clear principles for the structuring of a fair and just fiscal policy.

Interspersed with the lectures provided on these different themes will be workshops on practical skills such as public speaking, policy making, political virtues and statesmanship. Learning and team-building activities, as well as social time, will complete a daily routine framed by communal meals, prayer and liturgy.

The charity has been securing sponsorships from various organisations and trusts to cover the costs of the participants, in order to make this course free of any financial burden. However, the current pandemic has not made this process easy, and several places remain awaiting sponsorship.

The charity will therefore not only be very grateful for any further support it receives towards meeting the costs of the course, but particularly for prayers offered for the course’s success. Please do also signpost your local Catholic secondary schools and Lower Sixth students to the details below!

For more information about the course and for the Information and Application Pack, visit www.christianheritagecentre.com/clf or contact [email protected]