‘The Chinese have a wonderful intelligence, natural and acute,’ he wrote, ’from which, if we could teach our sciences, not only would they have great success among these eminent men, but it would also be a means of introducing them easily to our holy law and they would never forget such a benefit.’

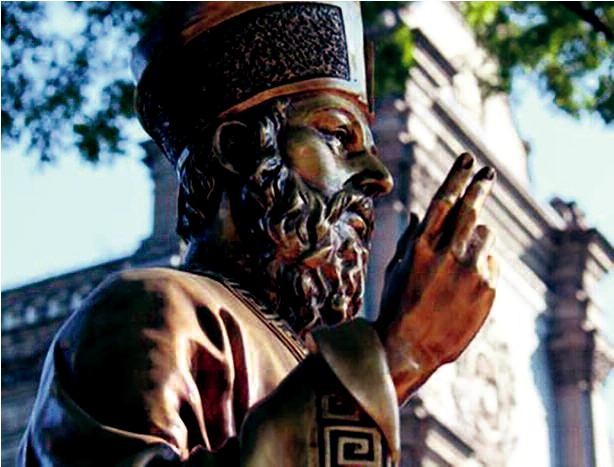

Unlike his more aggressive Portuguese and Spanish counterparts, whose presence in Macao became a source of conflict with the Chinese authorities, Ricci’s admiring embrace of Chinese culture, language and customs, gradually gave him a following in many circles.

Ricci’s publication of his world map, the Mappamondo, along with translations of Western classical scholarship; his knowledge of astronomy and mathematics; his decision to import hitherto unknown musical instruments, such as the harpsichord, along with Venetian prisms and mechanical clocks, all gained him acceptance and, despite occasional attempts to close the missions, the ultimate forbearance of the Emperor.

His reasoned approach also bore spiritual fruit – with the Jesuit’s work blessed by healings and miracles. In his diary, Ricci wrote: ‘From morning to night, I am kept busy discussing the doctrines of our faith. Many desire to forsake their idols and become Christians’.

Ricci brought the hugely admired Plantin Bible to China – eight gilded folio volumes with printed parallel texts in Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek and Latin. His True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven was printed and distributed widely, drawing heavily on Aquinas but also appropriating Confucian ideas to bolster the Christian cause.

He brilliantly repositioned the important Chinese custom of ancestor worship by tracing everything back to ‘the first ancestor’ – the Creator, the Lord of Heaven. It was a later repudiation by the Holy See of this interpretation which would end the Emperor’s patronage of the mission and the expulsion of Jesuits.