Friday 7th September 2018

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

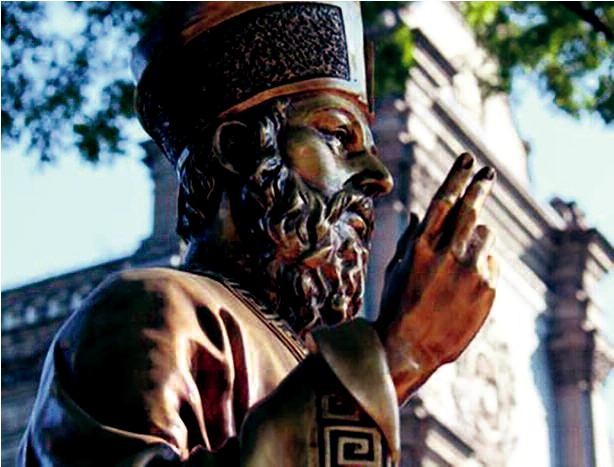

China’s attacks on Christianity will fail while the spirit of Mateo Ricci lives on

Lord Alton of Liverpool

Last week, two Catholic priests, Fr Wang Yiqin and Fr Li Shidong were forcibly removed from their Chinese parishes for holding a youth summer camp that had not been authorised by China’s Communist authorities.

Increasing attacks on religious faith – against Chinese Christians, Tibetan Buddhists and Muslim Uighurs – looks like part of a new Maoist Cultural Revolution. The shocking sight of bulldozed churches and mosques – including the obliteration of the famous Golden Lampstand Church in Shanxi Province – is reminiscent of Stalin’s destruction of Orthodox churches and monasteries.

Yet, where was the outrage to these events – including dramatic video of that 50,000 capacity church being dynamited?

This determined crackdown began in February when President Xi’s new religious regulations come into force. These require the registration of all religious bodies, which must be ‘Sinoised’ and freed from ‘foreign’ influences and rebuilt on ‘socialist’ principles. Intriguingly, the well cared for tomb, in Beijing, of a 16th century Italian Jesuit missionary, Mateo Ricci SJ – left untouched, on Mao’s own orders, during the Cultural Revolution’s desecration of the graves of foreigners – suggests that it must be possible for States to reach a proper accommodation with religion.

One of the rooms in the newly built Theodore House – part of the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst (CHC) – celebrates the memory of Matteo Ricci. The Trustees of the CHC believe Ricci’s own story is instructive and should give encouragement in the face of contemporary persecution.

The Cambridge scholar, Mary Laven, in Mission to China, charts Ricci’s encounter with China and her people. She reminds us that Christianity is not a new religion in China. In 635, in the seventh century, Olopen, a Nestorian monk, travelled to the Eastern city of Changan (today’s Xi’an); and there were other sporadic, later attempts (including that of St Francis Xavier), to take Christianity to China.

But it was Matteo Ricci’s arrival which would lead to more than 2,000 conversions and to the widespread dissemination of the Christian narrative. And it is Ricci’s intelligent approach – based on friendship and respect – which should inspire us today.

On reaching China the Europeans initially shaved their heads and dressed as monks but soon realised that by identifying with Buddhist and Taoist idolatry they were failing to reach the literati – the educated Confucian elite. So, Ricci chose instead to dress and behave as a Confucian scholar – engaging China’s culture and leadership through science, books and reason – fides et ratio.

‘The Chinese have a wonderful intelligence, natural and acute,’ he wrote, ’from which, if we could teach our sciences, not only would they have great success among these eminent men, but it would also be a means of introducing them easily to our holy law and they would never forget such a benefit.’

Unlike his more aggressive Portuguese and Spanish counterparts, whose presence in Macao became a source of conflict with the Chinese authorities, Ricci’s admiring embrace of Chinese culture, language and customs, gradually gave him a following in many circles.

Ricci’s publication of his world map, the Mappamondo, along with translations of Western classical scholarship; his knowledge of astronomy and mathematics; his decision to import hitherto unknown musical instruments, such as the harpsichord, along with Venetian prisms and mechanical clocks, all gained him acceptance and, despite occasional attempts to close the missions, the ultimate forbearance of the Emperor.

His reasoned approach also bore spiritual fruit – with the Jesuit’s work blessed by healings and miracles. In his diary, Ricci wrote: ‘From morning to night, I am kept busy discussing the doctrines of our faith. Many desire to forsake their idols and become Christians’.

Ricci brought the hugely admired Plantin Bible to China – eight gilded folio volumes with printed parallel texts in Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek and Latin. His True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven was printed and distributed widely, drawing heavily on Aquinas but also appropriating Confucian ideas to bolster the Christian cause.

He brilliantly repositioned the important Chinese custom of ancestor worship by tracing everything back to ‘the first ancestor’ – the Creator, the Lord of Heaven. It was a later repudiation by the Holy See of this interpretation which would end the Emperor’s patronage of the mission and the expulsion of Jesuits.

In 1742 Pope Benedict XIV terminated any further discussion of the issue; a decree which was repealed only in 1938. Pope John XXIII, in his encyclical Princeps Pastorum, rehabilitated Ricci’s methodology and reputation saying Ricci should be “the model of missionaries.” Ricci’s other 16th century writings were his Catechism and a treatise On Friendship, building on Confucius’ belief, expressed in the Analects, that ‘To have friends coming from distant places – is that not delightful?’ Simultaneously Ricci introduced his readers to Cicero’s assertion that “the reasons for friendship are reciprocal need and mutual help.” Amicitia perfecta – perfect friendship – was, for Ricci, the highest of ideals. Certainly the Chinese came to value him as a true friend.

On his death, on 11th May 1610, he was uniquely accorded a burial site in Beijing by the Emperor – which, according to Laven was “an extraordinary coup, which testified to the success of nearly 30 years of careful networking and diplomacy.”

His legacy included astronomical instruments and installations brought by Jesuits to Beijing, which – like his tomb – remained untouched even during China’s disastrous Cultural Revolution.

An even more enduring memory has been Ricci’s admirable willingness to find ways through difficult situations and his innate respect for Chinese culture and civilisation – something to inspire both the Church and the Chinese authorities. Chinese leaders should study the story of Matteo Ricci but they should also study compelling research that shows that those societies that respect religious freedom are the most prosperous and the most stable.

China is a great country with much to offer the world – but it needs to think more deeply about the self- inflicted damage it is doing by trying to eliminate religious freedom and by suppressing Christianity. A country built only on materialism will become a country without a soul – and that, in turn, would be an unhappy society lacking in harmony or respect – values every society needs.

Alienating millions of religious believers, rather than harnessing them in Ricci’s spirit of friendship, is both wrong-headed and short-sighted.

The Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst will be playing its part in telling the story of China’s persecuted Christians and in ensuring that they are not forgotten.