11th October 2021

Our Lady, the Rosary and Europe

Stefan Kaminski

Since the end of the 19th century, October has been dedicated to the Holy Rosary. Of all the devotions to Our Lady, the rosary is the most notable, of course. Indeed, the place of the Rosary at the forefront of Marian devotion particularly, and Catholic prayer generally, is reinforced by the fact of the Church having established a universal Feast of the Holy Rosary, which is celebrated on the seventh of October, and from which grew the dedication of the entire month to this prayer.

In this month of October then, it’s worth calling to mind both the origins of the Rosary as well as its historical role in the fortunes of Christian Europe. Although the challenges facing Christians and Catholics today have a different aspect and character, the nature of those challenges to the Faith remains the same.

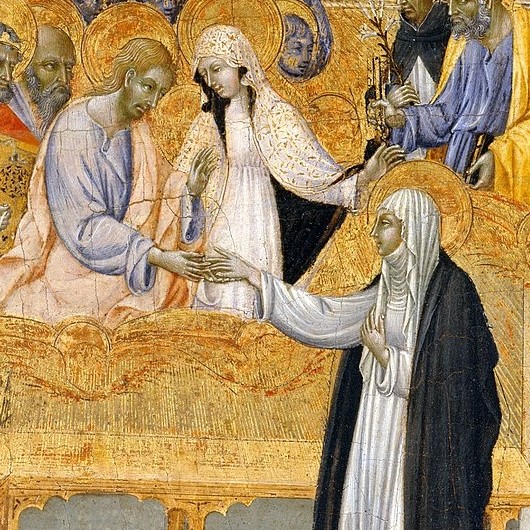

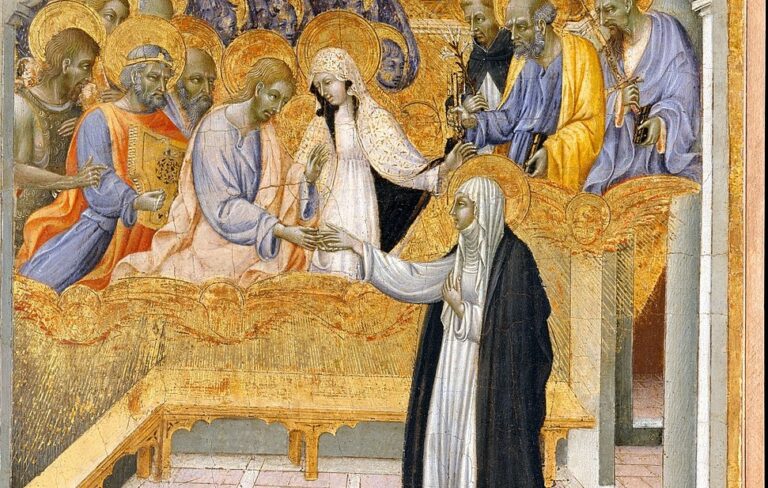

Tradition tells us that it was St Dominic who received the Rosary from Our Lady in response to his plea for help in the face of the Albigensian heresy. Surfacing near Toulouse in the eleventh century, this corruption of the Christian faith took a particular hold in the southern French territories in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Albigensian heresy, though formally speaking long extinct, is not entirely irrelevant to today’s dialogue with a secular world.

The Albigenses held a belief in two opposing principles of existence: a good principle and an evil principle. They held the good principle to be the creator of the spiritual world, and the evil principle to be the creator of the material world. Thus, a fundamental rupture with the Christian faith takes place: the good principle is not all-powerful, being co-equal to the evil principle; and material creation is not good, being the work of the evil principle, and therefore not redeemable. Morally speaking, this resulted in a dualistic view of the human person, where the body – and all activity related to it – seen as something to be supressed and denied.

On the face of it, this does not seem to bear much similarity to today’s attitudes to the body, which simultaneously exalt bodily desire, justifying all forms of its expression, and degrade the body by objectifying it. Underneath however, lies the same problem: an inability to grasp and to accept the intrinsic goodness of the body’s natural ordering. If for the Albigenses the material world was evil, today’s secular world sees the material world as meaningless. Thus, where the Albigenses repressed, we manipulate according to our desires. And we forget that these desires remain profoundly marked by sin.

In the midst of the division and conflict caused by this heresy, St Dominic presented the Rosary to the Catholic faithful as an antidote. This might strike some as slightly strange, if we consider St Dominic as a great preacher and founder of an order that has a particular charism for teaching. Why not combat an error of thinking with an irrefutable piece of writing or speaking? And here lies a two-fold lesson.

Firstly, our rational knowledge or understanding of the faith can never be separated from the life of prayer. At both a corporate (i.e. the Church) and individual level, that which we pray informs that which we believe. This is summed up in the ancient axiom, lex orandi, lex credendi (the law prayed is the law believed). The rosary is a particularly powerful instrument in this respect, as it directs us to meditate on the key moments of the story of God’s Incarnation, Life, Death and Resurrection amongst us.

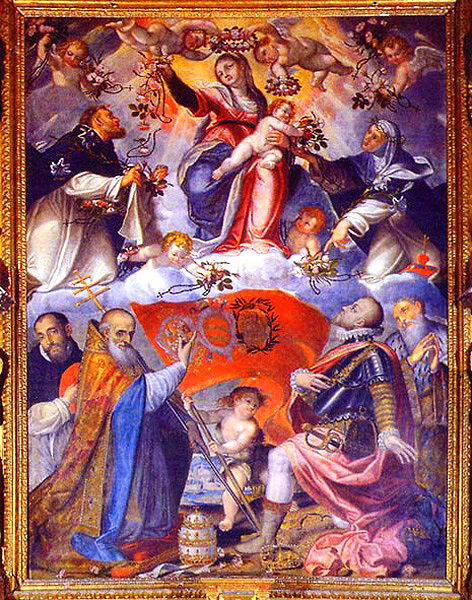

Secondly, Our Lady has a particular and active part to play in nurturing and defending the Church, of whom she is the Mother. An appeal to Mary was not just successful in the case of the Albigensians, where the Rosary was seen as securing their final defeat at the Battle of Muret in 1213, but has a strong track record since. Most notably is the Battle of Lepanto, where the threat of the Turkish empire overrunning and extinguishing Christian Europe was, and has ever since, been attributed to the plethora of rosaries offered publicly and privately in response to Pope Pius V’s call for prayer.

Less-known, but equally important, was the previous Turkish attempt to gain a foothold in Europe in 1565, with the Great Siege of Malta. Again, after much Marian invocation, the Turkish fleet – the largest recorded in history to that date – sailed away from Malta with its army and weaponry, never to return, on the Feast of Our Lady’s birthday. Similarly, the victories of Christendom at the Battles of Vienna in 1683 and of Peterwardein (Hungary) in 1716 against the same Turkish aggressors were attributed to the intercession of the Virgin Mary. Numerous other histories of victory or protection, not just physical but also spiritual, exist, which this article will have to leave to the reader to discover for themselves!

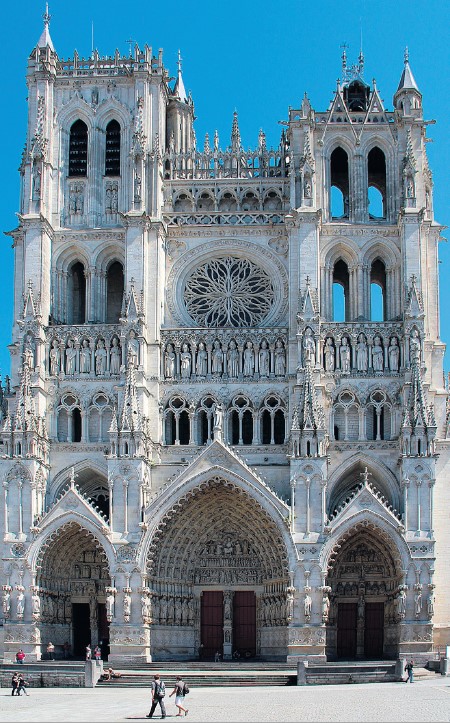

Although the Faith and its practice may be on something of a decline in modern-day Western Europe, a powerful reminder of our historical devotion to Our Lady and her concern for us remains emblazoned on the very flag of the European Union. Aside from the devout Catholics who were behind the original EU project – such as Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman, Alcide de Gasperi – the designer of the flag, Arsene Heitz, told Lourdes magazine how his inspiration had come from the Book of Revelation: “a woman clothed with the sun… and a crown of twelve stars on her head”. Coincidentally (or perhaps God-incidentally!), the flag was adopted on 8th December 1955: the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Our Lady of Europe, pray for us!