15 October 2024

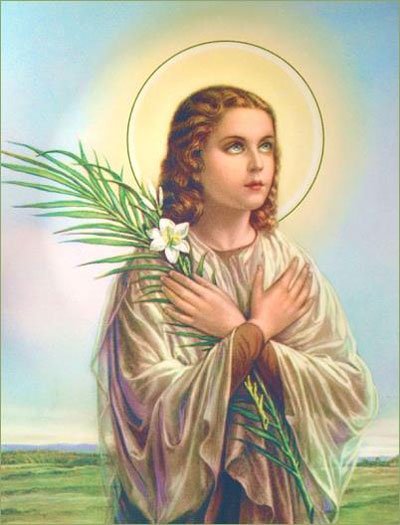

Saint Maria Goretti | The Year of Prayer

By Joey Belleza, PhD (Cantab.)

Prayer is ordered not only to our own personal good, but for the good of our neighbours. For this reason, the central part of Mass has the people ask that the sacrifice might be made acceptable to God “for our good and the good of all his holy Church.” The graces which flow from the Mass can extend to all people, and are meant to bring everyone, from the holiest saint to the most unrepentant sinner, into communion with God. The story of Saint Maria Goretti is a most remarkable example of how the effects of prayer can extend to even one who, in one moment in life, might have been seen as an enemy of Christ and his Gospel.

The third of seven children, Maria was devoutly dedicated to the Lord, living with her family in impoverished conditions. When she was nine, her father died, forcing the family to live in a shared house with the Serenelli family. On 5 July 1902, one of the Serenelli sons, the troubled nineteen year old Alessandro, took a lustful liking to the young Maria. In a moment when they were alone at the house, Alessandro threatened to stab Maria if she did not submit to his advances. She refused, warning Alessandro of his mortal sin. Still, the young man persisted, attempting to force himself on her, choking her as she resisted with all her might. Finally, in a fit of rage, Alessandro stabbed Maria fourteen times. Maria, gravely wounded, reached for the door, but Alessandro stabbed her three more times.

Maria was rushed to the hospital and Alessandro was arrested. She survived incredibly for a day, with the surgeons amazed that she had not succumbed to so many wounds to her heart and lungs. However, her resistance was only temporary. She breathed her last on 6 July, but not before pronouncing, “I forgive Alessandro Serenelli, and I want him with me in heaven forever.”

Instead of a life sentence, the court imposed a thirty year sentence, acknowledging Alessandro’s harsh upbringing and consequent mental illness. He was unrepentant for three years, until a bishop visited him. After this visit, he wrote to the bishop, saying how Maria appeared to him in a dream, in which she gave him white lilies which burned in his hand. From that day, Alessandro repented of the murder. He was released after twenty-seven years, whereupon he immediately sought out Maria’s mother and begged her forgiveness. She responded, “If my daughter can forgive him, who am I to withhold forgiveness?”

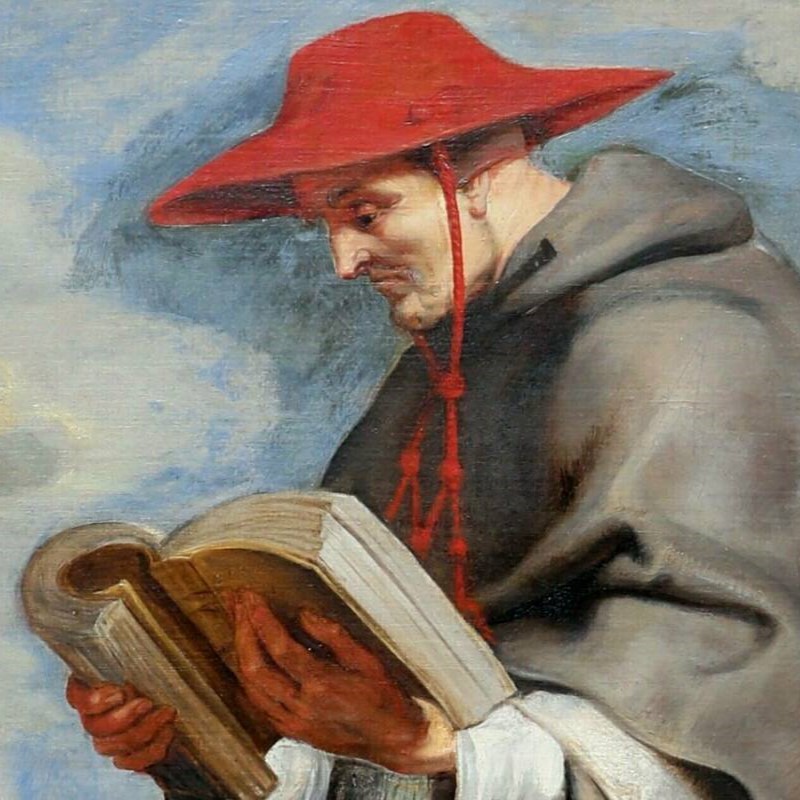

In 1947, Pius XII beatified Maria, and after a rapid canonization process, raised her to the altars in 1950. Her canonization Mass is remarkable in that not only the parents of the martyr were present, but also her murderer. Alessandro Serenelli, now a lay brother of the Capuchin Franciscans, joined the throng of Christian faithful praising God for the gift of Maria’s example.

Christ taught us to love our enemies, and Maria Goretti followed this commandment perfectly. May we also pray for those who wrong us, that they too might return to the loving embrace of God.