Friday 2nd October 2020

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

Homage to the Martyrs at Deepdale

David Gorman

David Gorman looks back 50 years to when 20,000 flocked to Preston’s Deepdale Stadium for Mass to celebrate the Canonisation of the Forty Martyrs, a quarter of whom came from Lancashire.

The cause for the canonisation of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, which eventually took place on 25th October 1970, stretches its roots back to the mid-19th Century.

Following the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850, Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman and Cardinal Henry Manning led a campaign for the recognition of those who had been Martyred for the faith.

Just a year previously, in 1849, Frederick William Faber had written the rousing hymn Faith of Our Fathers in memory of the Martyrs. Born and raised an Anglican, Faber converted and was ordained a priest, later becoming an Oratorian Father.

By 1935 nearly 200 Reformation Martyrs had been beatified, earning the title ‘Blessed’, but only two, John Fisher and Thomas More, had been canonised; both on 19 May 1935 by Pope Pius XI.

Following the end of the Second World War, the cause, which had been largely dormant for some time, was gradually revived and, in December 1960, the names

of 34 English and six Welsh Martyrs were submitted to the Sacred Congregation of Rites by Cardinal William Godfrey, Archbishop of Westminster. All had been Martyred between 1535 and 1679. The list of names was drawn up in consultation with the Bishops of England and Wales and an attempt was made to ensure the list reflected a spread of social status and religious rank, together with a geographical spread and the existence of a well-established devotion.

Of the 40, 33 were Priests (20 religious and 13 secular) and seven were lay people. It is worth noting that around a quarter of these Mar-tyrs came from within the historic boundaries of the County Palatine of Lancashire, a reminder, albeit a poignant one, that the region remained a true stronghold of the faith despite the persecutions and difficulties that brought.

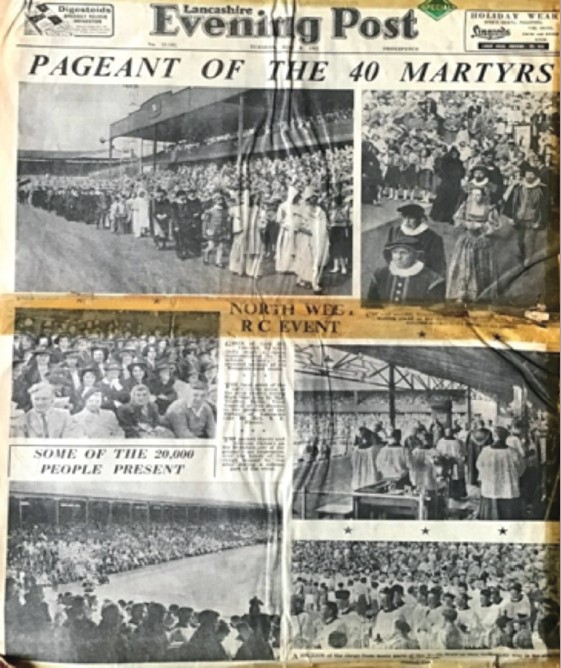

On 24th May 1961, the re-opening of the cause was formally decreed by Pope John XXIII. It was no surprise, therefore, that once the list of 40 names had been submitted, and the decree issued, the Diocese of Lancaster was quick off the mark in organising a rally in support of the cause. The rally took place on Sunday 2nd July 1961 at Deepdale, home to Preston North End, and was attended by more than 20,000 people including over 200 clergy.

Parishioners, school children, scouts, guides, cubs and brownies all processed through the streets of Preston from their respective churches to the stadium while others, from parishes further afield, arrived by coach. The Lancashire Evening Post reported that: ‘It started back in the parishes where three huge processions based on St Joseph’s, St Ignatius’ and St Gregory’s formed and walked through the streets with banners and bands to converge at Deepdale’.

A ‘Pageant of the Martyrs’ took place with 40 individuals each dressed as a martyr in the colourful costumes associated with the Tudor and Stuart periods. Narrators announced brief details of each martyr’s life and death, and once all were assembled on the dais ‘they presented a huge tableau, strangely set in a modern football stand, of figures who suffered the strife and religious persecution in England and Wales 400 years ago’.

The pageant was followed by Pontifical High Mass celebrated by Monsignor Thomas Eaton, the Vicar General of the diocese, in the presence of Bishop Thomas Flynn of Lancaster.

For the canonisation to proceed it was necessary for two miracles, granted through the intercession of the 40 as a group, to be recognised. A list of 24 miracles was collated and submitted by the English and Welsh bishops and, after careful examination, two of these were chosen for further scrutiny. The Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints granted a special dispensation whereby it was decided, subject to Papal approval, that one of the two miracles would be sufficient to allow the canonisation of all 40 Martyrs to proceed. This was the “cure of a young mother affected with a malignant tumour (fibrosarcoma) in the left scapula, a cure which the Medical Council had judged gradual, perfect, constant and unaccountable on the natural plane”.

On 4th May 1970 Pope Paul VI confirmed the “preternatural character of this cure brought about by God at the intercession of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and Wales”. The path was now open for the canonisation to take place on a date to be set, and thirty-four English and six Welsh Martyrs were submitted to the Sacred Congregation of Rites by Cardinal William Godfrey, Archbishop of Westminster. All had been Martyred between 1535 and 1679. The list of names was drawn up in consultation with the Bishops of England and Wales and an attempt was made to ensure the list reflected a spread of social status and religious rank, together with a geographical spread and the existence of a well-established devotion.

However, there was concern in some quarters about the effect the canonisation might have on the ecumenical agenda. In November 1969, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Michael Ramsey, had “expressed his apprehension that this canonisation might rekindle animosity and polemics detriment to the ecumenical spirit that has characterised the efforts of the Churches recently”.

It was clear, however, that the majority of people within both faiths supported the canonisation and, on 18th May 1970, Pope Paul VI declared, during a consistory, that the canonisation would take place on 25th October that year “pointing out, with serene frankness and great charity, the ecumenical value of this Cause, also laying particular stress on the fact that we need the example of these Martyrs particularly today not only because the Christian religion is still exposed to violent persecution in various parts of the world, but also because at a time when the theories of materialism and naturalism are constantly gaining ground and threatening to destroy the spiritual heritage of our civilization, the 40 Martyrs – men and women from all walks of life – who did not hesitate to sacrifice their lives in obedience to the dictates of conscience and the divine will, stand out as noble witnesses to human dignity and freedom”.

Some 10,000 English and Welsh pilgrims, together with the bishops of England and Wales and representative bishops from Scotland and Ireland, were among the large congregation which attended the canonisation Mass at St Peter’s. Special guests included descendants of many of the martyrs, including the Duke of Norfolk, England and Wales’s most senior Catholic layman and himself a collateral descendant of the soon to be St Philip Howard. In recognition of the unique significance of the event for English and Welsh Catholics, the Maestro Perpetuo of the Sistine Chapel Choir, which would normally sing at all canonisation Masses, agreed that the Westminster Cathedral Choir could sing in its place. The Catholic writer, Auberon Waugh, described the canonisation as “the biggest moment for English Catholicism since Catholic emancipation”.

This article is from a series published in the Catholic Voice of Lancaster this month, commemorating the 50th anniversary of canonisation of the Forty Martyrs.