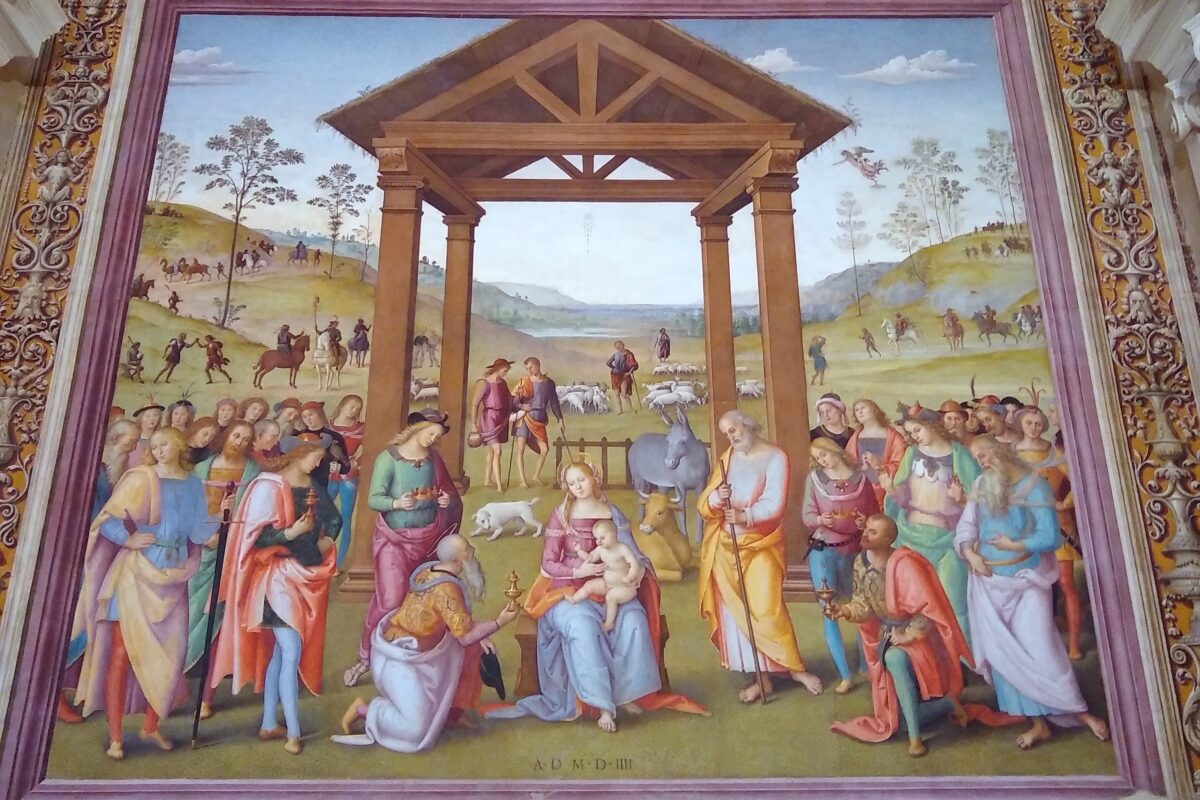

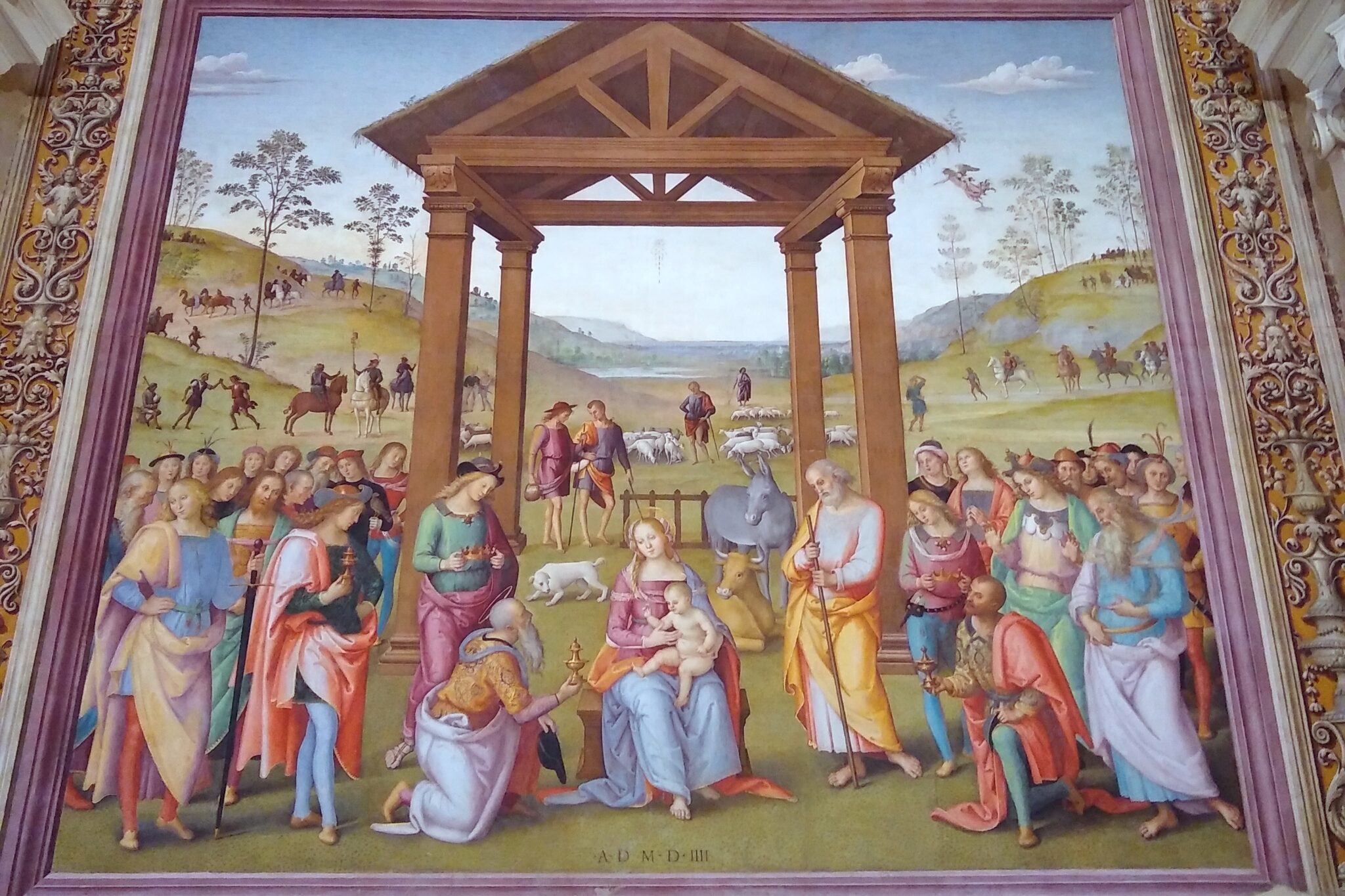

Perugino’s Adoration of the Magi in Citta’ delle Pieve, Italy (as opposed to the one in Perugia) contains a curious detail which is easily overlooked at first glance. In the dim light of the small Oratory that houses this painting, the vibrant colours of the principal figures in the foreground pop out and create an almost 3D effect. The observer’s gaze is drawn across the breadth of the painting by the various garments of the ten or so persons that flank the child Jesus in the centre. One is conscious of the depth and activity that stretches away behind this first row of figures, but the colours readily draw the eye back to the primary scene. It is not easy for the eye to then drop down to the protagonists’ feet, which are very much where you expect them to be. By virtue of their sensibly-coloured footwear, they do not demand any particular attention: that is, until one notices that the feet of some of these important people are bare.

The feet that have most obviously exposed themselves to the elements are those of Mary and Joseph. Perhaps a nod to their humble state, in view of the bare-footed shepherds that hover in the background, and in contrast to the calced extremities of their noble visitors? The homogeneity of the garments across this front row of figures would suggest not. Closer examination reveals that one more of these principal figures is also bare-footed: the bearded gentlemen at the far right. Why should he not have worn some sandals on this visit?

If, by some astute observation (or perhaps at the prompt of a helpful guide), one compares this man with the discalced Holy Family, and then particularly with the figure of Joseph, one starts to notice some strange similarities: a perfect parallel in bodily posture, from the angle of the head down to the distribution of weight and position of the feet; an identical facial profile and features; a reflection of each other’s expression. The only distinguishing feature, other than the colour of the garments, is that the man’s beard is much fuller and longer, and is distinctly double-stranded.

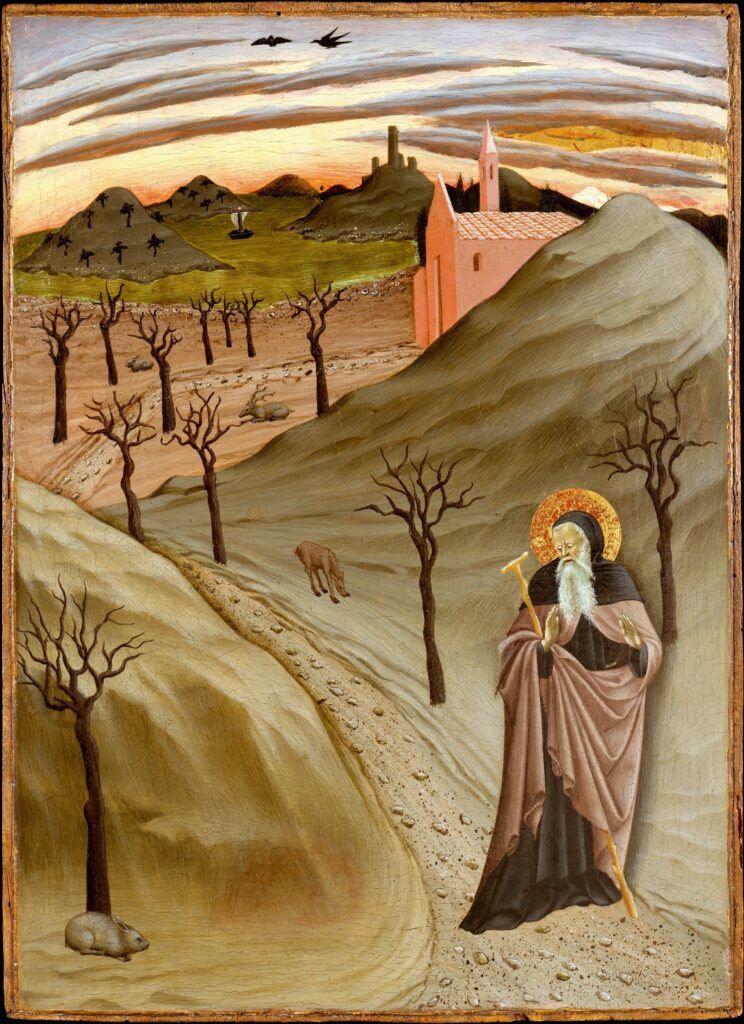

The only clue that can be claimed with certainty is that this particular beard is clearly used by Perugino in other of his paintings on the figure of God the Father. If we are to suppose, then, that Perugino did indeed intend this figure as the Heavenly Father, one can also note the gold girdle around his waist – typically depicting sovereignty or royalty – and the celestial blue of his undergarment – a classical indicator of a spiritual being.

This striking relation between the figures of Joseph and God the Father immediately calls to mind St Paul’s letter to the Ephesians: “For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named” (3:14-15). The painting appears to express precisely this: Jesus’ foster-faster, Joseph, is shadowed by the real Father, who manifests His presence discreetly in the background and at the same time somehow lends authority to the figure of Joseph. Joseph’s persona thus takes on a fuller sense when one realises that his fatherhood, though temporal, is exercised in the name of the Father.

Joseph, who plays such a strong, yet silent role before and through the infancy of Jesus, quietly disappears from the Gospels as the Christ emerges into the maturity of His humanity and the fullness of His divine mission. Yet his presence is a reminder that God the Son was not born into some extraordinary situation, even if His Incarnation was an extraordinary event. The Divine Saviour was inserted into the ordinary and regular pattern of the nuclear family – father and mother – surrounded by their extended family and relations.

Given the non-biological nature of Joseph’s fatherhood, one might ask whether there is any deeper meaning to his role than simply that of fostering the child and providing stability and support to the mother. Perugino, if we have interpreted his painting correctly, seems to very much think there is. And indeed, more authoritative support comes from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Their long genealogies trace Jesus’ ancestry through each generation from Adam through to Joseph, passing through the lineage of Abraham and his Israelite descendants, encompassing kings and prostitutes alike.

Fans of Tolkien will be all-too-familiar with those long pages in The Lord of the Rings that are preoccupied with tracing the lineage of Frodo Baggins, Aragorn or one of the Dwarves. Indeed, ancestry is an absolutely critical part of all Tolkien’s writings that tell the story of his fantasy world, beginning with its creation, as told in the Silmarillion, through several epochs until the ‘redemption’ of Middle-Earth with the defeat of Sauron and the destruction of the Ring of Power.

In his mythical vision of reality, Tolkien merely reflects what is divinely and humanly true; namely, that the human person is not an isolated ego, a self-defined construct, or a morally-autonomous being. The human person has an origin and a destiny, is given their existence and context, and is called to act for the concrete good of his neighbours.

Thus, at a legal and social level, Joseph’s importance is in providing Jesus with a crucial part of His human ‘identity’, through which He is inserted into a chain of parents and progeny. This is deliberately traced right back to its very origins, pointing us back to the Father, after whom every family is named. It similarly evokes future progeny, the generation of which is the primary purpose of the family. In the case of Christ, that progeny is potentially every person throughout human history, who through faith in Him, are all called as adopted children of the same Father.

The Church’s vision of the human family is thus grounded in the nuclear family for a good reason: the family is the context and means intended by God for the flourishing of humanity. God Himself assumed humanity in this context, and whilst He ‘only’ adopted an earthly father, the figure of Joseph speaks powerfully of the more important and fundamental reality that is true of every family. This is the same truth that St Paul is at pains to point out in his letter to the Ephesians, and has been recognised since the early Church Fathers: Fatherhood, properly speaking, is a reality that only belongs to God. God is Father of all because He is creator of all. In the same way that the very existence of every being depends on the supreme Existence, the fatherhood (as expressed in the complementary, generative power of both sexes) of the human person only and ever has any meaning as a reflection of and cooperation with the Divine Fatherhood.

Inserted into the specific strand of Joseph’s ancestry, the Holy Family raises the stakes for all human families. No longer is the family simply the font of earthly life, but it is now joined to the Divine project of Redemption. The human family not only remains a co-operator in the mystery of creation (to paraphrase St John Paul II), participating with God in the creation of human persons: it is now an embodiment of the mystical marriage between Christ and His Church, and its primary task is now to generate children for the Kingdom of God. As Perugino depicts so beautifully, human fatherhood is a task that is given by God, and answerable for to Him alone.