24 December 2023

Christmas Eve 2023: A Reflection

By Joey Belleza

Around the world, from Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome to innumerable humbler parishes, the Mass of Christmas night is preceded by an ancient Latin chant called the Kalenda, also known as the Christmas Proclamation. Beginning with the creation of the world, the Kalenda lists the watershed moments of sacred and secular history in chronological order, culminating in the proclamation of Jesus’ birth. From Creation to the Flood, from Abraham to Moses, from King David to Caesar Augustus, the text is a kind of “countdown,” situating the Incarnation in relation to real events and real people, before finally announcing the birth of Christ according to the flesh as the central, climactic event of all human history. However, separating the long list of events and the actual mention of the birth of Christ, there lies a short, five word phrase, almost inserted as a parenthetical remark, whose brevity veils its profundity: toto Orbe in pace composito—“the whole world being at peace”.

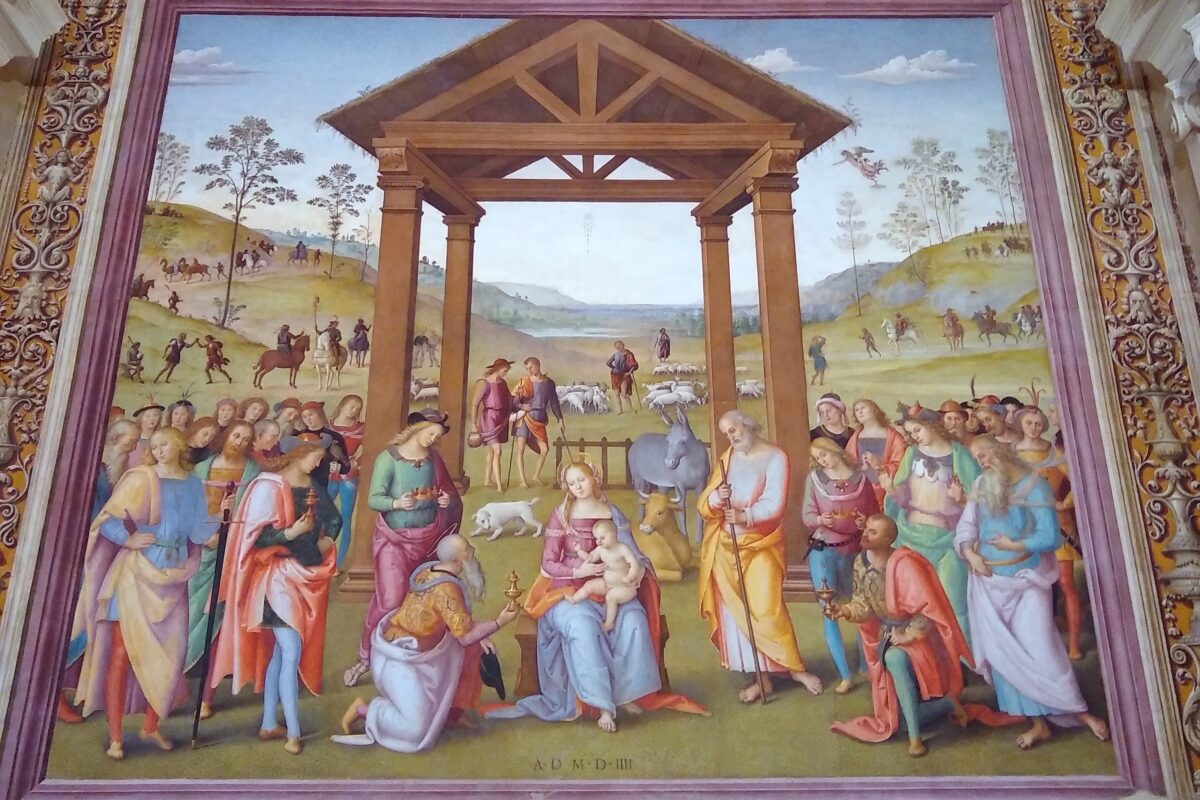

Toto Orbe in pace composito: yes, Christ entered the world at a time of a great peace seemingly prepared for him. He was born at the beginning of the so-called Pax Romana in which the Roman Empire reached the zenith of its expansion, attaining hitherto unparalleled prosperity and security. The Jewish people, although subjects of the Empire, remained free to worship the One God of Israel and were exempt from offering sacrifices to the gods of Rome—a privilege denied to all other conquered peoples.[1] The Israelites once more had a king—although he was a puppet—and the elite of Jewish society even held full rights as Roman citizens. The tumultuous trials of previous generations seemed surpassed. Against this historical backdrop, in that little town of Bethlehem, while the world lay asleep “in heavenly peace”, the Christ child is born of the Virgin Mary, wrapped in swaddling clothes, and laid in a manger. Shepherds and angels alike come to adore him, while wise kings from far-off lands bring him precious gifts and do him homage. Of that momentous occasion, in that silent and holy night, we can say: vere toto Orbe in pace composito—truly the whole world was at peace.

Of course, the Pax Romana, that worldly peace guaranteed only by military might, did not last; the unfolding of history will reveal the common fate of all empires ancient and new. Jerusalem’s peace with the Caesars will end with a bloody uprising to culminate in the destruction of the Temple. The tranquillity of the first Christmas would not long endure: when Herod learns of the newborn king foretold by the prophets, he commands the massacre of Bethlehem’s sons to protect his throne, and the infant Prince of Peace will flee to exile in Egypt. As an adult, Christ will not go untouched by the violence of earthly life; his people will reject him, the disciples will abandon him, the Sanhedrin will condemn him, and Pilate will execute him. By worldly measures, he is but one of countless other insurgents crushed under Rome’s imperial heel. But all this will come later; at least for this night, when he enters the world as a “holy infant so tender and mild,” “all is calm; all is bright”; in other words, toto Orbe in pace composito.

Year after year, we run through the gauntlet of life’s tribulations. Troubles at work, at home, among friends and family, continue to plague us, test us, and overwhelm us to the point that at times, we question our life choices and perhaps even think them mistaken. But in the time of year when the nights grow longer and the days grow colder, the frantic pace of life seems to slow down bit by bit, until the earth itself appears to stop. We Christians look forward to this season all year long. We consciously set aside time—however brief—away from our daily struggles, resentments, and grudges. We happily come to our friends and family in a spirit of love and reconciliation, and join together to celebrate the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ. We can recall remarkable events like the Christmas Truce of 1914, when German and British soldiers spontaneously emerged from the mud and blood of the trenches, sharing soccer and schnapps, chocolate and cheer, in a brief flicker of peace on earth while the world was at war.[2] Amidst our own decorations, the greeting cards and gifts, the Christmas carols, the dark days, and the cold weather that marks the close of the calendar year, we find that for a few sacred moments in this holy night, the ancient words of the Kalenda once again ring true: toto Orbe in pace composito—the whole world is at peace. As all of creation stops to rest for the winter, the whole Church also pauses to genuflect in thanksgiving for the Incarnation—wherefore in every Christmas Mass throughout the world, Catholics kneel during the Creed as we profess Christ, incarnate of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, and made man. Here and now, as during the first Christmas, we prepare a peaceful stage for the arrival of the Christ child, who comes yet again to fill our hearts with divine gladness.

I’m sure the irony of our situation isn’t lost on anyone: we celebrate the birth of the Prince of Peace as conflict rages across the globe. In Libya, Mali, Sudan, and the Central African Republic, the traces of old colonial empires bleed with the rise of newer nationalist movements. From the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, drones and missiles and fast attack craft imperil the free movement of civilian merchant ships. In the South China Sea, Chinese and Philippine vessels tensely square off in disputed territorial waters. An emboldened Venezuela threatens to unilaterally annex the land of neighbouring Guyana. Civil wars in Syria and Myanmar continue unabated, while Armenia and Azerbaijan are no closer to resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis. In the sands of Gaza and on the banks of the Dnipro, Palestinians and Israelis, Russians and Ukrainians, warriors young and old, vigilant as the shepherds of Bethlehem, endure another sleepless night, illuminated not by Christmas lamps but by rockets and gunfire. We who might count ourselves lucky to live far from these regions of conflict cannot consider ourselves immune to danger; recent riots in Ireland and the mass shooting in Prague show us how the fragile peace of Christmas can crumble in an instant. The experience of the pandemic has also taught us how, by mere ministerial fiat, the power of the state might be wielded against churches and against Christian men and women of good will who desire nothing more than to adore the Incarnate Lord.

Thanks be to God that we can gather tonight as his holy people to celebrate the ineffable gift of his Incarnation. For on this night, we remember and proclaim that God, from the heights of divinity, has immersed Himself completely into our humanity, even unto the depths of our sin, so that when we falter and fail, He is already there in the darkness, waiting to raise us. Thus, even in the bitterest crucible of war, the “glories of his righteousness and wonders of his love” are ever present. Let all Christians therefore take hope from the words of the prophet Isaiah, whose prophecy is fulfilled on this very night: “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; upon those who dwelt in the land of gloom a light has shone.”[3]

That light is, as the Kalenda says, “Jesus Christ, eternal God and Son of the eternal Father”[4] who, through that “marvellous exchange”[5] of his divinity for our mortality, made our mortality a path to divinity. Tonight, “let ev’ry heart prepare him room,” so that the splendour of Christmas might dispel whatever darkness remains within us. We pray for concord among nations, reconciliation among ourselves, and tranquillity in our hearts, for in doing so, we each do our part to help bring about, as the song goes, “Peace on earth and mercy mild/God and sinners reconcil’d”. Thus, when we look back on Christmas 2023, with God’s help we will be able to say, with no hint of irony: toto Orbe in pace composito—that at least for a fleeting moment in the dark of night, in spite of the countless conflicts which afflict our age, Christ the Light appeared to us while the whole world was at peace.

In the midst of our uncertain times, the messenger of the Lord tells us tonight as he told the shepherds of Bethlehem: “Do not be afraid; for behold, I proclaim to you good news of great joy… today in the city of David a saviour has been born for you who is Christ and Lord.”[6] Tonight, therefore, we reawaken the great hymn of the angels, dormant since we began our Advent pilgrimage, and in concert with the celestial choirs, we acclaim as they did two thousand years ago, saying, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to those on whom his favour rests.”[7]

Our Lady, Queen of Peace, pray for us. Amen.

________________________

[1] See Tertullian’s Apologeticum, ch. XXI, in which he responds to charges that Christianity, illegal in his time, “hides under the umbrella of a certain well-known and legal religion [i.e., Judaism], or otherwise under its own presumption” (sub umbraculo insignissimae religionis, certe licitae, aliquid propriae praesumptionis abscondat).

[2] From the diary of German Lieutenant Johannes Niemann, Christmas 1914

[3] Isaiah 9:1

[4] From the Kalenda: “…Iesus Christus, aeternus Deus, aeternique Patris Filius, mundum volens adventu suo piissimo consecrare…”

[5] 1st Vespers, Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God; antiphonum ad Psalmum: “O admirabile commercium (O marvelous exchange): Creator generis humani, animatum corpus sumens de Virgine nasci dignatus est; et, precedens homo sine semine, largitus est nobis suam Deitatem”; see also the Prayer over the Gifts for Christmas Mass at Night, 1962 Missale Romanum: “”…ut, tua gratia largiente, per haec sacrosancta commercia…”

[6] Luke 2:10-11

[7] Luke 2:14