Friday 7th July 2023

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

Icon Writing: My journey from Syria to Byzantium

Schaher Rhomaei

Schaher Rhomaei shares how he began to explore the extraordinary art of ‘icon writing’ -and how icons can be a ‘visual Gospel’ to inspire a deeper and more profound faith.

My first memory of icons takes me back to my tender years at St John the Baptist Church; a small Byzantine Greek Melkite church in Ma’arouneh, which means ‘small cave’ in Aramaic. This mountainous suburb of Damascus is a place of natural biblical and spiritual beauty. It was Elijah’s last abode before ascending into Heaven.

From this place and time, I began a journey of reflected prayer through the beauty of icons: an encounter with the Divine. One icon that stands out for me in particular was a wooden panel depicting Our Lady tenderly holding her Son on her lap. Somehow, the aura of mystery surrounding this icon created a sacred space for contemplating the striking image of the humble Mother and the Saviour child, which remained with me throughout my childhood.

The word ‘Icon’ comes from the Ancient Greek (εἰκών/eikṓn) meaning ‘image or resemblance.’ The term was, in fact, coined by Plato, in relation to his theory of knowledge. According to the philosopher, real knowledge is to be found in the intelligible world of Ideas, which is reflected to some degree, as per a shadow, in the physical world. Likewise, in Christian art, the word “icon” has become synonymous with the depiction of divine subjects and the sacred figures of those in the heavenly world. Icons thus not only communicate a profound and sacred significance, but also create a powerful sense of prayerfulness.

Icons Hold Deep Spiritual Meaning

In the Eastern Church generally and the Syrian Church particularly, icons are an essential pillar of the Christian faith, holding deep spiritual meaning. They serve as windows through which one can approach the Creator, not only by praying and prostrating before Him. but also by seeking help or forgiveness. Indeed, the Eastern Church understands icons as a visual gospel, proclaiming in colours and images all that is uttered in words and written in syllables (cf. Council of Constantinople)

According to historians, Christian art originated and developed in Syria before this ancient, original, and spiritual artform was exported to Egypt and Mesopotamia, and then to the wider world. The journey from Syria to Egypt to

Byzantium gave birth to different styles of icons: ‘Syrian’ in Syria, ‘Coptic’ in Egypt and in Byzantium ‘the Byzantine art.’ The latter describes the process of creating icons as one of ‘writing’ rather than ‘painting’ – an iconographer is a ‘writer’ not a ‘painter’ – and we ‘read’ an icon rather than view or ‘see’ it.

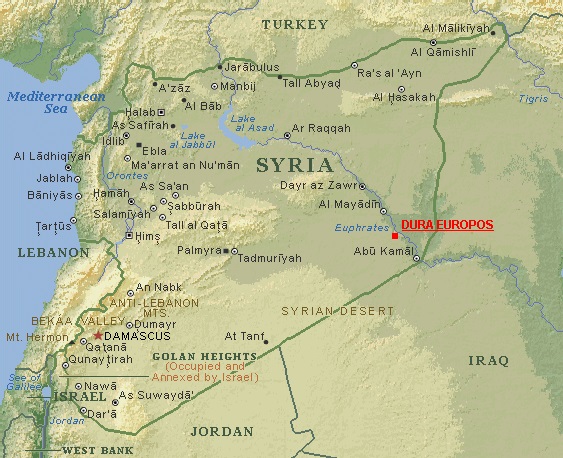

At Dura-Europos near the Euphrates River in the Syrian Desert lie two living ‘witnesses’ to early iconography. First, there is the baptismal room of a private house that became the first home church, with murals painted in 232-56 AD, decades before Emperor Constantine recognised Christianity. Then there is a synagogue dating from the third century, with brightly painted walls depicting famous scenes from the Old Testament. Although the artistry of Dura-Europos might seem simple in nature and battered due to age, fighting, destruction and the like, yet it is astounding in its beauty and depth.

Those depictions emerged from the early Christian imagination, from a faith alive with wonder. They give us a precious insight into the emotions and desires of those isolated faithful on their early journey. It was their way of reaching out to express their faith

with confidence. Their belief and trust in Christ were represented quite differently compared to that of, for example, the Christian art of the Renaissance, where great emphasis was placed on an aesthetic and grandiose depiction

A Contemplative Experience

My journey into icon writing began during what seemed to be an eternal lockdown. This period of transition and discernment drew me deeper into exploring this extraordinary art. Initially, as part of a reflection on art and spirituality to celebrate Eastertide, I wrote my first icon, ‘Christ is the Light.’ Following that and whilst celebrating Pentecost, another icon followed: ‘Mary in the Cenacle.’ Both were written in a style that resembled that of the early Christians: simple and expressive. The aim was to understand the mystery of Christ and His Mother’s being as they reach out in love, keeping the light aflame in our hearts. I envisaged them as radiant, humble, and modestly dressed with an expression of intensity and invitation. Out of this contemplative experience, two images conceived and set in darkness emerged, of such humanity and yet of such majesty.

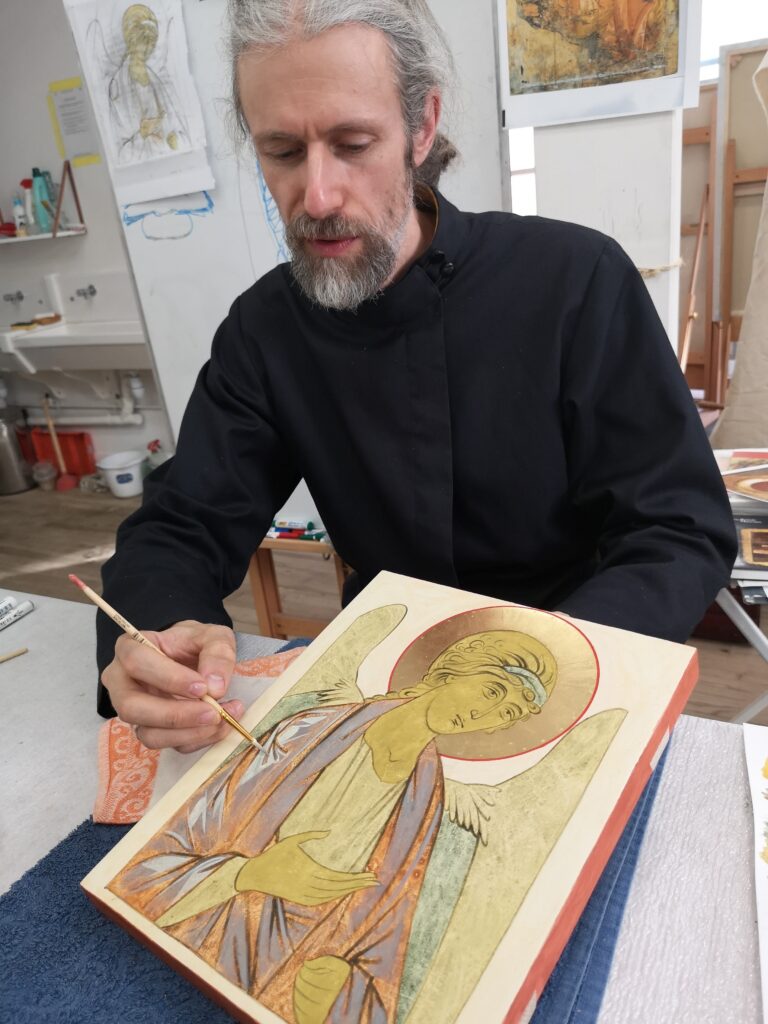

In the following year, I completed more icons using oil, but it was not until this year that I embarked on a new journey: that of exploring the Byzantine style using pigments and egg tempera. Drawn by the spirituality of Master Vladislav Andrejev at the Prosopon School of Iconology in the US, I took part in an icon writing course at the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst, facilitated by his Andrejev’s son, Nikita, who is a master in his own right. The theme of the workshop was ‘Our Lady of Tenderness.’ I found the whole experience a complex piece of utmost beauty and delicacy.

To save time, the wooden panels were already prepared. The first stage was applying the gold leaf onto the halos, then the initial underpaint tone, which covers the faces and other parts of the body, and the application of a dark yellow/green pigment called Sankir, thus creating the shadow areas. Here, shadows are not of a physical source as such, but rather ethereal. Similarly, the light areas in an icon indicate the divine nature and not a reflection of the sun. Stage by stage, the image builds as other layers are applied, always lighter than the one before. Patience and thoroughness are required throughout the whole process; from laying the gold leaf, getting the right measurements of pigment and egg tempera, to the right brush strokes. Each step is crucial and has its own logic, as well as consequences if not done in a methodical way. I must admit that, unlike my previous work, this experience was not merely painting, but building.

Taking A Leap Of Faith

We were fifteen people attending this course, some writing their first, second, or even seventh icon. It was my first workshop and although quite apprehensive about the process and outcome, I took a leap of faith and dived into exploring this wonderful art form, allowing the Holy Spirit to guide and inspire me as I went along. It was touching to see how some of the other experienced writers, aside from the tutor, mentored the beginners in their struggles. They gently offered advice and even helped to salvage areas that at times seemed almost like a battlefield.

My piece was no exception. I faced a mess right at the start because I applied too much clay, which is used as an adhesive for gold leaf. It was too wet and this meant that the leaf would not stick to the halos and kept peeling. My thanks go to David, a fellow participant who kindly rectified the catastrophe at once. His meticulous application of gold leaf and the right pressure did wonders and was like a sign of light and hope that helped me to go on.

In contemplating this recent experience, three profound insights surfaced for me. The first relates to how the harmony and symmetry of composition must be visible everywhere in the icon, from the poise of the figures to the flow of drapery. These carefully-drawn and harmonious straight lines come to life as flowing lines of Divine energy. Secondly, the role of luminosity in an icon is suggestive of the Holy Spirit within the subject, constantly renewing and creating life. And lastly, the words of my little cousin still echo in my head today, as she sat next to me in that very same church of St John the Baptist, and whispered with a slight giggle and pure innocence: “This is you and your mother….” Indeed, Mary’s presence in icons conveys a unique sense of motherhood. She is a source of inspiration, hope, comfort, and support to those in need of her help.

For the Christian Heritage Centre’s iconography course, visit http://christianheritagecentre.com/events/iconography-course/