Friday 3rd August 2018

19th century visionary asks all to be ecologists

The Very Rev. Damian Howard, SJ

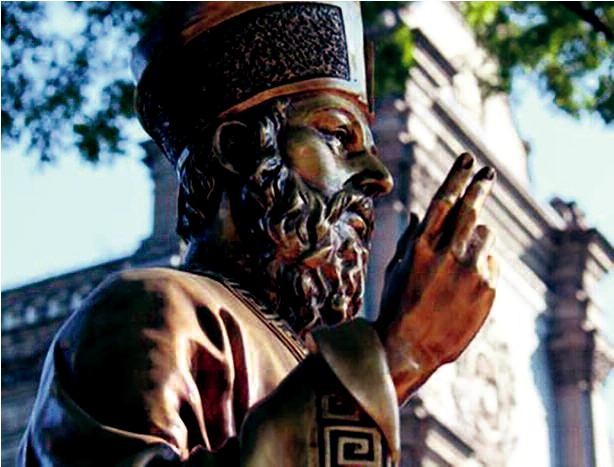

Beneath a glass panel in the floor of the Wakefield Museum you’ll find a large caiman, a kind of South American alligator. It is a preserved specimen and part of a collection made by Charles Waterton, an alumnus of Stonyhurst College.

Waterton made several trips to British Guiana (now Guyana) in the early 19th century, building an impressive collection of preserved animals which he later presented to his old school. In 1966, the bulk of this collection was placed on display in Wakefield, and since then has often been back on display at Stonyhurst.

Central to Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ is the idea of ‘integral ecology’. This recognises that humans are part of a vast network of living beings on the planet upon which we are wholly dependent. That network is itself simply a part of a wider series of relationships with the entire creation: the light of the sun, the waters of the oceans, the minerals we build with, and the air that we breathe.

Pope Francis here joins his voice to those who call us to recognise that our current irresponsible use of the gifts of creation runs the risk of making the Earth uninhabitable by ourselves and other species. We have a duty to care for ‘our common home’.

There is something new here for Christian faith to grapple with. An old-fashioned but distorted outlook took the mandate of Genesis 1:28 (‘Be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth and subdue it. Be masters of the fish of the sea, the birds of heaven and all the living creatures that move on earth’) as permission for human beings to dominate the rest of creation, exploiting it as we see fit to meet our needs. Those areas where men and women had not yet settled were ‘wilderness’, the habitat of evil spirits, and destined to be tamed and brought under human control.

Over the centuries, forests were cleared for agriculture, animals domesticated for food, rivers dammed and mines dug. Human beings were fruitful and multiplied, spreading across the globe, seizing the natural resources for themselves.

By the 19th century, in the wake of the industrial revolution, the harmful effects of this unchecked exploitation were becoming clear. Pollution poisoned waterways and air, slums in the ever-growing cities and diseases such as cholera and TB were rife. Concern about this situation grew and, alongside this, some began to look for alternative lifestyles and modes of development.

Charles Waterton was an early example of this quest. In 1824 he returned from his last visit to Guiana to Walton Hall, his family home in Yorkshire. Over the next few years, he built a nine-foot wall stretching for three miles around his estate, and ran it as a nature reserve, with a lake for wildfowl. He prosecuted a local soapworks when effluent from their factory seeped into the water supply. He wrote extensively on natural history and conservation. These achievements were recognised by Sir Richard Attenborough when he opened a new display of Waterton’s work in Wakefield in 2013.

It may have taken the Church a little while to latch on to these concerns, but when she did she spoke firmly on the matter. By 1971, Pope Paul VI, in his encyclical Octogesima Adveniens, was able to write that ‘due to an ill-considered exploitation of nature, humanity runs the risk of destroying it and becoming in turn a victim of this degradation’ – lines quoted later in Laudato Si’.

Ecumenically, a movement which had been known as Justice and Peace was, by the 1980s, commonly employing the acronym JPIC – justice, peace, and the integrity of creation. This change recognised the fact that there could not be a just and peaceful world unless the Earth’s resources were shared equally. More, it acknowledged that these resources were finite, and it would not be possible for the developing nations to exploit them to the extent that the western countries had been doing.

No-one is surprised these days when a papal document is addressed not exclusively to the Catholic faithful but to all men and women of good will, of all faiths and none; and that is the audience Laudato Si’ has in mind, too. This commitment to work for an integral ecology is a prime example of an area in which believers find themselves collaborating with all sorts of different people. Some of them, indeed, are far ahead of most Christians in their engagement and experience. As well as something precious to offer, we have much to learn. Indeed, the scale of the crisis facing humanity is such that it will require as many as possible to work together if they are to be addressed adequately.

For the Jesuits in Britain, the much-regretted closure of Heythrop College, a college of the University of London, has presented an opportunity to explore new avenues, inspired by the teaching of Pope Francis. Heythrop offered excellent teaching and research in philosophy and theology for nearly 50 years. It is now our intention to redeploy some personnel and finance which once served Heythrop to the new intellectual task of coming to a deeper understanding of integral ecology.

It is important to note that this concept, as Pope Francis expounds in Laudato Si’, is not simply about climate change or recycling, important as these topics are. It means more; it is nothing less than a renewed vision of what it is to be a follower of Christ in the 21st century. Pope Francis wants us to take part in a bold cultural revolution, to reimagine society and our very civilisation in the light of the insight that “all things are connected”.

I believe that this new vision has the potential to bring diverse groups of people together, both inside and outside the Church, maybe even helping us overcome the divisions which still remain as the legacy of the Reformation.

British Jesuits are currently working in three ways. The first is to be a research institute, linked to Campion Hall, our Permanent Private Hall in the University of Oxford. Addressing the challenges we face will require careful interdisciplinary study. This institute will be able to pursue rigorous theological and philosophical research into the situation we face and help us to imagine alternative ways of living, more at- tuned to the Gospel.

The second element will be a centre, most likely in London, where we can provide education for people in the Church and beyond on these issues, and the Christian response to them. This will be aimed particularly at young adults, and is likely to include at least one Master’s level university course. Students will be able to draw on the resources of the Heythrop library, which is one of the largest libraries of Catholic theology and philosophy in the country.

These two academic strands will be complemented by a more practical project, offering people the opportunity to get involved in ecological and other social justice projects, while being guided in ways of reflecting on their involvement and integrating this into their faith. Pope Francis has spoken repeatedly of discernment, and looks to the Jesuits, among others, to help all to further develop this spiritual practice. In time it may prove possible to set up communities which will be able to offer witness to living more harmoniously with the rest of creation.

All of this may seem to be a long way from Charles Waterton and the preserved animals he presented to Stonyhurst. But he was one of the first to recognise the dangers of regarding creation as nothing more than a resource to be exploited for human need – and greed. His collections have inspired generations of young people to think about their place in the natural world, and in each generation since some have gone on to make this study their life’s work.

It is my hope that the new project the Jesuits in Britain are developing will be similarly inspiring, leading many more to commit themselves to caring for our common home for the greater glory of God.