Friday 6th September 2019

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

Communicating the faith through stories of the saints and martyrs

Sr Emanuela Edwards looks at storytelling and how, even in our hi-tech digital age, it remains a powerful way to communicate the faith.

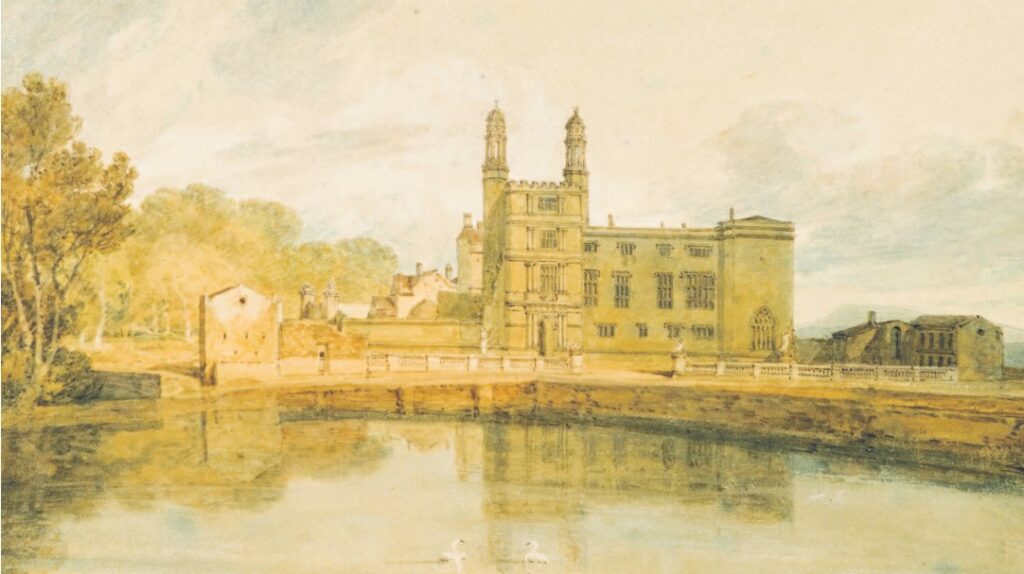

One of the greatest challenges, if not the greatest, for the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst is the communication of the faith to the people of our time. The Christian faith we possess, and the roots of our Christian Heritage must be rendered interesting and challenging and be communicated to everyone. It should be done in such a way that it can reinforce the faith of those who believe, whilst at the same time reach out to the periphery to speak of God’s love for all even to those who would not usually be interested!

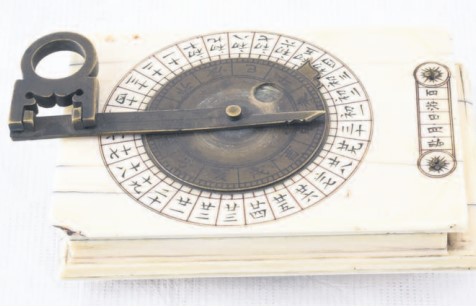

One way of achieving this aim is to use the ancient art of storytelling. Since primitive times, stories have been used to transmit important truths, events and lessons to successive generations. In fact, the faith was originally handed on by the Apostles who testified or told the story of what they witnessed and learned from Christ. Artefacts and relics, like those in the Stonyhurst Collection, physically bring the stories of the martyrs and saints into proximity to those who look upon the objects. Pope Leo I asked, “why should the mind toil when the sight instructs” and indeed, looking at these artefacts and explaining their story presents an opportunity to recount the Christian faith in a captivating way.

Writing in the 4th Century Tertullian said, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the faith”. Encountering the stories of the lives of the saints and martyrs who have shaped our Christian Heritage sows the seeds of the faith in successive generations. Each artefact in the Stonyhurst Collections works like a silent sermon because it testifies to the life and witness of the martyr in question making their stories enter the present time and touch the life of the person viewing the object perhaps causing them to consider its lesson. Therefore, the stories of the Saints and martyrs become living lessons in the faith that can teach and inspire new generations hopefully calling them to a deeper conversion.

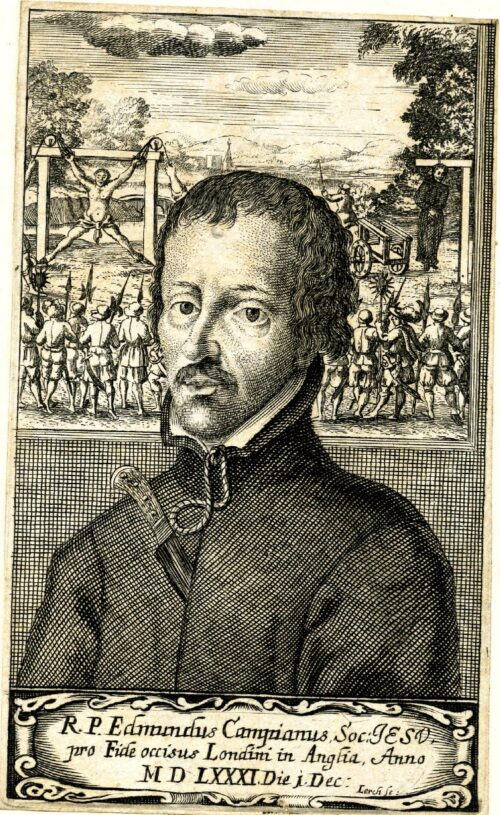

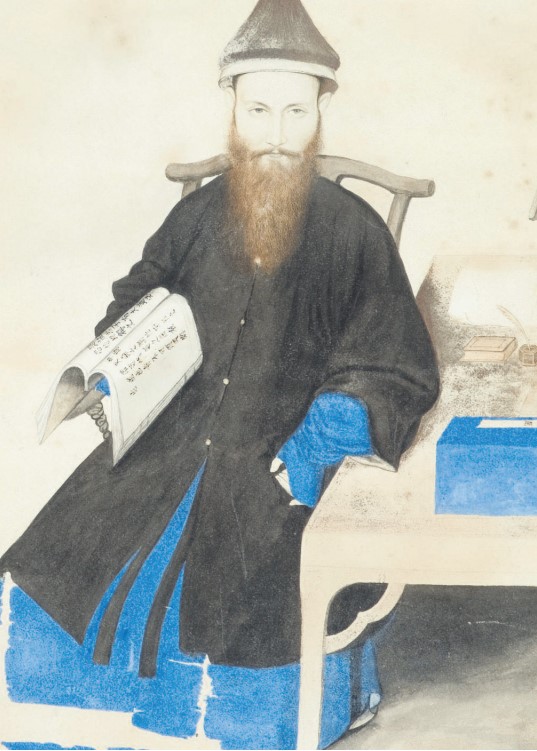

One of the most striking stories in the Collections is told by the relic of the rope that bound St Edmund Campion to the hurdle on which he was dragged through the streets of London before his execution. (The actual relic is the property of the British Jesuit Province on loan to Stonyhurst College). That rope tells the story of a Priest who, on penalty of death, nevertheless came to England in 1580 to preach the Gospel, confess and offer the Sacrifice of the Holy Mass to the Catholics driven underground in order to practice their faith. He preached and disseminated his famous Decem Rationes – ten reasons demonstrating the truth of the Catholic religion and was eventually captured, imprisoned and tortured before his execution at Tyburn on the 1st December 1581. His story raises an interesting question: why did St Edmund not yield to the tortures and inducements to conform in order to save his life? By word and deed St Edmund most eloquently testified that the Catholic faith is worth dying for. He did not change the course of his life as he knew that a seed must die to yield fruit (cfr. Jn 12:24). Today, that fruit is harvested in the hearts of those who are told of this heroic Priest whose behaviour was inspired by the truth of Christ and are brought into contact with the faith he died to proclaim.

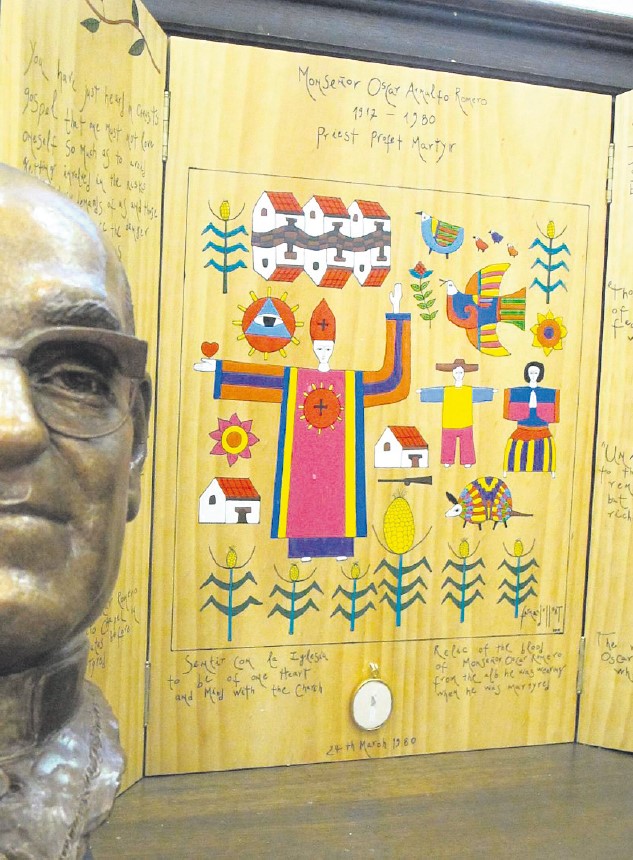

The Collections also have a part of the vestment worn by St Oscar Romero who was killed in El Salvador in 1980 whilst offering the Holy Mass. This relic serves as a poignant reminder that Christian martyrdom is not an ancient reality but that this story still continues today.

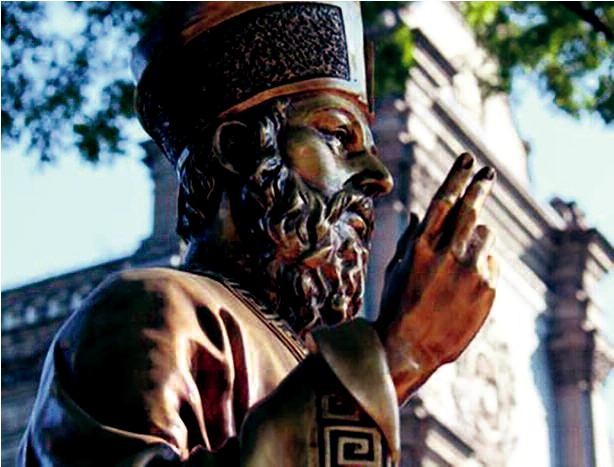

Another English martyr whose story is told through the artefacts and relics of the Stonyhurst Collections is St Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor of England, who was martyred for refusing to take the Oath of Succession in 1535. This saint’s story demonstrates how artefacts and relics can show the faith of the saint rather than just tell of it hence providing a more powerful source of Christian inspiration. During the homily for the Canonisation of St Thomas More, Pope Pius XI spoke of the “ardour of his prayer” and the “practice of those penances by which he kept his body in subjection.” Indeed, this can be borne out by close inspection of his golden crucifix with spikes on the back that was worn as a penance by the Saint. Here we learn something of the intimate life of the Saint that was founded on a deep prayer life. In fact, it was this intimacy with Christ that strengthened him to resist the tears of his wife and children over his condemnation and to be, “content to lose goods, land and life as well rather than to swear against his conscience”. In this way, the stories of the Saints also teach us that Christian witness is borne through a closeness to Christ in prayer and is not the fruit of the passing moment.

It is hoped that a visit to this beautiful collection will make the stories of the Saints vibrate in our hearts giving us a living lesson in the truths of the faith. May the stories of the martyrs strengthen us by imparting the knowledge of the faith and the inspiration to live it so that we too can witness to our rich Christian heritage that shaped our past and partake in its reconstruction in our own time.

Sr Emanuela Edwards

Missionaries of Divine Revelation

Trustee of the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst

[email protected]

www.mdrevelation.org