Friday 3rd March 2017

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

For Hopkins nature was charged with God’s glory

Fr Samuel Burke OP

Over recent months, a series of articles in this newspaper has showcased the great treasures of the new Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst.

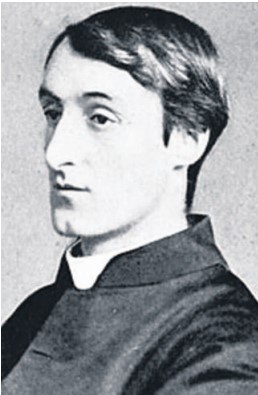

The Stonyhurst Collections serve to explain, cherish and bring to life the inspiring history of the Christian faith in Britain. This final article explores the inspiration that the beautiful countryside of the Ribble Valley, which surrounds Stonyhurst, provided to the Jesuit priest and poet, Father Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Hopkins’ poetry is highly distinctive in theme. It brims with the conviction that the natural world is, as he put it, “word, expression, news of God.” To look upon creation was, for Hopkins, to see God’s glorious majesty or what he called the ‘inscape’ of things: an aesthetic experience which was “near at hand” for those who “had eyes to see it… it could be called out everywhere again”.

He took delight in seeing things as God made them, however small and commonplace. Confiding in his journal, he once wrote, ‘I do not think I have ever seen anything more beautiful than the bluebell I have been looking at. I know the beauty of our Lord by it.’

In an earlier letter written to a friend whilst he was studying Classics at Balliol College, Oxford, Hopkins provides another insight into his playful curiosity and his deep love of the natural world, strikingly evident in the poetry he would later write: ‘I have particular periods of admiration for particular things in Nature – for a certain time I am astonished at the beauty of a tree, its shape, its effect.

‘Then, when the passions so to speak has subsided, it is consigned to my treasury of explored beauty, while something new takes it place in my enthusiasm.’

And it was a ‘treasury of explored beauty’ that he amply amassed during his three periods at Stonyhurst in Lancashire, even if his poetic output whilst stationed there was relatively modest.

With child-like enthusiasm, Hopkins records in his diary his first experience of the arresting beauty of the place when he first arrived at ‘the seminary’ (properly called St Mary’s Hall, now the Preparatory School at Stonyhurst) as a Jesuit Scholastic in early September 1870, aged 26 for his studies in philosophy.

On the night of his arrival, after being shown to his room at the front of the building on the top floor, Hopkins remained awake until dawn in order to witness the ‘beautiful range of moors dappled with light and shade’, a panoramic view that included the majestic Pendle Hill, which he likens to a ‘world-wielding shoulder’.

Hopkins had arrived at the seminary early, in fact. With the other scholastics on holiday, and classes not due to start until the following month, GMH had the leisure of exploring the spectacular environs of Stonyhurst, which he did with abandon, for as he would write in a later poem ‘…nature is never spent; There lives the dearest freshness deep down things’.

He roamed hills, woodlands and Lancashire meadows ‘smeared yellow with buttercups and bright squares of rapefield in the landscape’. Hopkin’s way of seeing the world was deeply influenced by the writings of the Franciscan theologian, Duns Scotus.

A journal entry for 3rd August 1872 records his discovery of Scotus’ Scriptum Oxoniense super Sententiis in the Badeley library on the Isle of Man during a vacation he took from Stonyhurst.

Hopkins describes his find as ‘a mercy from God’ and comments that he was ‘flush with a new stroke of enthusiasm.’ He was to write of his fondness for the theologian in a later poem, Duns Scotus’ Oxford.

This first stay at St Mary’s Hall, Stonyhurst, as a Jesuit scholastic, lasted three years (1870-1873). In those days it was an austere regime, which at times proved challenging for the young man.

Hopkins attended two one hour lectures in the morning and did a further three hours of study from 5 – 8pm. Religious observances and time for recreation were fitted in around these fixed times, and the only permitted conversation was at mealtimes.

Although he might have expected to become a teacher at one of the Jesuit schools, on completing his philosophy studies, Hopkins was initially sent back to Manresa, the Jesuit Noviciate House at Roehampton, to serve as Professor of Rhetoric, before proceeding to St Bueno’s where he was subsequently ordained as a priest.

Later, as a priest, he twice returned to Stonyhurst. His second stay was for a His third lasted for just over a year from September 1882 to December 1883, when – though sad to leave – he was called to University College Dublin. On both occasions he taught Classics as a tutor to the Gentlemen Philosophers, a group of Catholic laymen who received their university education at Stonyhurst.

As Catholics were forbidden to take degrees at Oxford and Cambridge, and indeed forbidden from doing so by Catholic bishops, they enrolled for external Bachelors degrees at the University of London. During the time he spent at Stonyhurst, Hopkins continued to deepen his love of the world around him. As part of his interest in God’s created order, Hopkins developed a great interest in astronomical matters, facilitated by the fine observatory at Stonyhurst, which provided research for the Vatican Observatory and is still in use today.

He writes poetic descriptions of the peculiar sunsets he saw there: ‘A bright sunset lines the clouds so that their brims look like gold, brass, bronze, or steel. It fetches out those dazzling flecks and spangles which people call fish-scales. It gives to a mackerel or dappled cloudrack the appearance of quilted crimson silk, or a ploughed field glazed with crimson ice.’

It wasn’t just the sun which caught his attention. He would find beauty — “the grandeur of God” — in all manner of places, some of them fairly unlikely. Stories abound of his eccentric behaviour at Stonyhurst, such as the time when he hung over a frozen pond to observe bubbles trapped beneath the ice or was seen staring at the gravel outside St Mary’s Hall.

Hopkins had a particular love for “the three beautiful rivers” near Stonyhurst. One of them, the Calder, runs close to the nearby remains of a Cistercian monastery, Whalley Abbey. Another, the River Hodder, sits beneath the school in a thick wood and was used by Hopkins and others for bathing, even if precarious after heavy rainfall.

The third and most significant of these rivers, the River Ribble, gives its name to the Ribble Valley, the wider expanse that surrounds Stonyhurst and the eponymous poem, Ribblesdale, one of at least five poems which Hopkins wrote during his stays at Stonyhurst.

The poem tells how nature cannot speak for itself but must find its voice through a human translator, as it were. And, as the following verses demonstrate, few voices were as finely tuned as that of Hopkins:

Earth, sweet Earth, sweet landscape,

with leavés throng

And louchéd low grass, heaven

that dost appeal

To, with no tongue to plead,

no heart to feel;

That canst but only be, but dost

that long

Thou canst but be, but that thou

well dost;strong

Thy plea with him who dealt, nay

does now deal,

Thy lovely dale down thus and

thus bids reel

Thy river, and o’er gives all to

rack or wrong.

And what is Earth’s eye, tongue,

or heart else, where

Else, but in dear and dogged man?

– Ah, the heir

To his own selfbent so bound,so

tied to his turn,

To thriftless reave both our rich

round world bare

And none reck of world after,

this bids wear

Earth brows of such care, care

and dear concern.

Other poems he wrote at Stonyhurst comprise: The Wreck of the Eurydice, with resonances of his earlier and more confessional Wreck of the Deutschland; The May Magnificat and The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air we Breathe – two poems in honour of Our Lady, whose image was and remains prominent in various statues inside the building and grounds; as well as The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo. In that poem, Hopkins confronts the dreadful reality of the loss and decay of the beauty that he holds dear:

How to keep—is there any any, is

there none such, nowhere known some,

bow or brooch or braid or brace, lace,

latch or catch or key to keep

Back beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty,

beauty, … from vanishing away?

As the poem progresses, Hopkins proceeds to take solace in the beauty that lies ‘yonder’ in God, who is ‘beauty’s self and beauty’s giver’.

In the midst of a world marked by loss and decay, a walk in the countryside can do us untold good lifting our spirits as such rambles did for Hopkins.

The Christian Heritage Centre is establishing a Hopkins’ walking route around Stonyhurst in his memory to accompany the Tolkien Trail, already available.

On such pleasant walks, we can gaze upon the beauty around us and can say with Hopkins: ‘I walk, I lift up, I lift up heart, eyes / Down all that glory in the heavens to glean our Saviour’.