Hopkins' Stonyhurst poem to Our Lady:

Mary's importance for our spiritual lives

Walker Larson

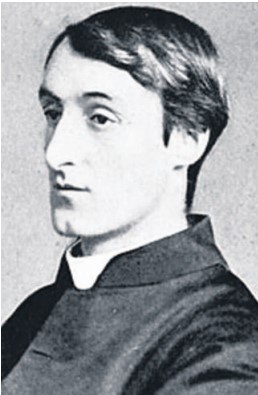

Gerard Manley Hopkins — convert, Jesuit priest, and one of the greatest Victorian poets — nurtured a deep love for the Blessed Virgin Mary, and that love found beautiful expression in his poem “The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe.” It was written in Stonyhurst in 1883 as part of a collection of poems in different languages that were to be hung near a statue of Our Lady in celebration of May Day.

The central conceit (a literary term meaning “extended metaphor”) of the poem is that Our Lady is to us in our spiritual lives what air is in our physical lives: critical, life-giving, all-encompassing, and gently filtering the light of God’s grace as it falls upon the soul like golden dew.

In this poem, Hopkins writes in iambic trimeter, which is a poetic meter that alternates unaccented and accented syllables, with three accents per line. Thus, the line “With mercy round and round” includes three accented syllables (“mer,” “round,” “round,”) that alternate with unaccented syllables. Hopkins frequently breaks the pattern in order to give it more life, better reflect everyday speech, and to avoid a monotonous tone.

Hopkins likes to jam-pack his lines with explosive and vibrant sounds, intense energy, and lyrical buoyancy, such as with the lines “goes home betwixt / The fleeciest, frailest-flixed / Snowflake; that’s fairly mixed.” These alliterative sounds spin out from the tongue like sparks above a campfire. They crackle with energy. Hopkins is a poet who loves the glowing richness and astonishing variety of reality, and his sometimes-surprising choice of words and sounds reflects that. He even developed his own poetic rhythm, used in much of his poetry, called “sprung rhythm,” as a more flexible pattern that allowed him to incorporate more sounds and beats into his lines.

In addition to these formal aspects, Hopkins makes use of imagery throughout the poem that reinforces its theme. He has interwoven symbolism of Our Lady, such as the frequent mention of the color blue, which is Mary’s color. “The glass-blue days”; “Blue be it: this blue heaven”; “This bath of blue and slake”; “How air is azured”; “Yet such sapphire-shot;” etc. The word “mother” also shows up frequently. Mary is ever-present in the language of these beautiful poetic lines, just as she is ever-present in our lives, playing “in grace her part / About man’s beating heart.”

One place that motherhood appears is in the opening of the poem. Hopkins begins by addressing something inanimate, the air itself (called an “apostrophe.”)

Wild air, world-mothering air,

Nestling me everywhere,

That each eyelash or hair

Girdles; goes home betwixt

The fleeciest, frailest-flixed

Snowflake; that’s fairly mixed

With, riddles, and is rife

In every least thing’s life

The poet focuses our attention on this ever-present yet invisible force that keeps us alive and enwraps us, “nestles” us at all times. He awakens us to the enigma of this remarkable reality that surrounds us — literally and figuratively — evoking the mystery of it with a word like “riddles,” and its universality by reminding us that even the “least thing’s life” depends upon this air. The smallest furry animal, with quickly vibrating, quivering chest, lives in and through the air, as do you and I.

Having opened our eyes to the wonder of this substance that is our “more than meat and drink,” he then initiates the comparison with Our Lady, saying that the air reminds him

Of her who not only

Gave God’s infinity

Dwindled to infancy

Welcome in womb and breast,

Birth, milk, and all the rest

But mothers each new grace

That does now reach our race—

Mary Immaculate.

How, precisely, is Our Lady like the air? Hopkins points out that her magnificent vocation is to “Let all God’s glory through, / God’s glory which would go / Through her and from her flow.” The implied comparison is clear: God is like the sun, which lights up all the world, and just as the sun’s rays comes to the earth and are diffused through the air, so is God’s love, mercy, and grace diffused to us through Mary. “I say that we are wound / With mercy round and round / As if with air.” And what is the channel of God’s mercy? The prayers of the Blessed Mother: “She, wild web, wondrous robe, / Mantles the guilty globe, / Since God has let dispense / Her prayer his providence.”

And just as we live by and through the invisible air, we live by and through the invisible grace mediated by Our Lady. Hopkins writes that we are “meant to share / her life as life does air.” And then he invokes the theological concept of Mary as Mediatrix of all graces:

If I have understood,

She holds high motherhood

Towards all our ghostly good

And plays in grace her part

About man’s beating heart,

Laying, like air’s fine flood,

The deathdance in his blood;

Yet no part but what will

Be Christ our Saviour still.

In other words, Our Lady, as some theologians have taught, constantly dispenses God’s graces to us, playing an intimate role in our spiritual life from moment to moment, her attentive love as close and constant to us as our own breathing.

As Bernadette Waterman War writes in “Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Blessed Virgin Mary,” “The poet reminds us of how we need grace as we need air, in order that we should not die. It is through Mary that God’s grace gives us life. He uses the figure of light for God’s grace, pointing out that without the air to filter it, sunlight would be too powerful for the human frame to bear.”

This last point — about the air’s tempering of the sun’s power to suit our strength — bears further reflection. Hopkins allows his imagination to run wild with what would happen without the air, how the sun’s full-bore intensity would blind the earth. The excess of light would turn our vision black, and we’d be steeped in dark:

Whereas did air not make

This bath of blue and slake

His fire, the sun would shake,

A blear and blinding ball

With blackness bound, and all

The thick stars round him roll

Flashing like flecks of coal,

Quartz-fret, or sparks of salt,

In grimy vasty vault.

The rich metaphorical imagery used in this passage also exemplifies Hopkins’ close and attentive study of “things,” how they look, feel, smell. All great poets are firstly great observers of the world, using their fine-tuned senses to penetrate into the nature of objects. Hopkins recreates the glowing of coals or the scattering of salt in our minds. It is Hopkins’s ability to render realistically the simple things of everyday life (coals, salt) and then tie them to the most sublime reaches of reality (God’s glory and grace) that forms a core part of his poetic genius. Through familiar images, Hopkins paints a picture of what unfiltered sunlight would be like (and by extension, what God’s glory would be to unredeemed man).

But Our Lady came “to mould / Those limbs like ours,” that is, to give God human form, a mild face to look upon that, in His hidden mortal life, would not blind us like the unfiltered blaze of the sun. God accommodated Himself to our condition, tempering the heat of His majesty through the Maid of Nazareth. “Her hand leaves his light / Sifted to suit our sight.”

We can follow Hopkins’ train of thought even further. It is through the Incarnation and Redemption, which were achieved through Mary’s cooperation, that we can hope to one day see God face to face, to stare into that brilliant, searing point of light like Dante at the end of the Divine Comedy, the lack of which makes one truly blind.

In light, dancing poetry, Hopkins has crafted a profound meditation on Mary and her role in our lives. He has carefully elaborated the various commonalities between Mary and the air, how both are ever with us, sustaining our life, and diffusing light all around us.