Friday 2nd August 2019

The CHC @ The Catholic Universe

Sacred places that speak of the Catholic Faith throughout different ages

Stefan Kaminski

Times change; people and places come and go. But the one Person a Christian relies on never changes or leaves: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever” (Hebrews 13:8). This fundamental conviction remains true for all Christians regardless of the age or society in which they live. It provides the same foundational inspiration for every authentic Christian life, and unites people throughout history – and indeed outside of history – in the hope of the Resurrection.

Up in Lancashire, within the space of about 10 miles (as the crow flies) one can visit the ruins of Whalley Abbey, the Shrine of Ladyewell at Fernyhalgh and Stonyhurst College. Each of these speaks in a particular way of a different era and dimension of the Catholic faith: each place witnesses to individuals and communities that bore out the conviction expressed by St Paul at various times and in various walks of life.

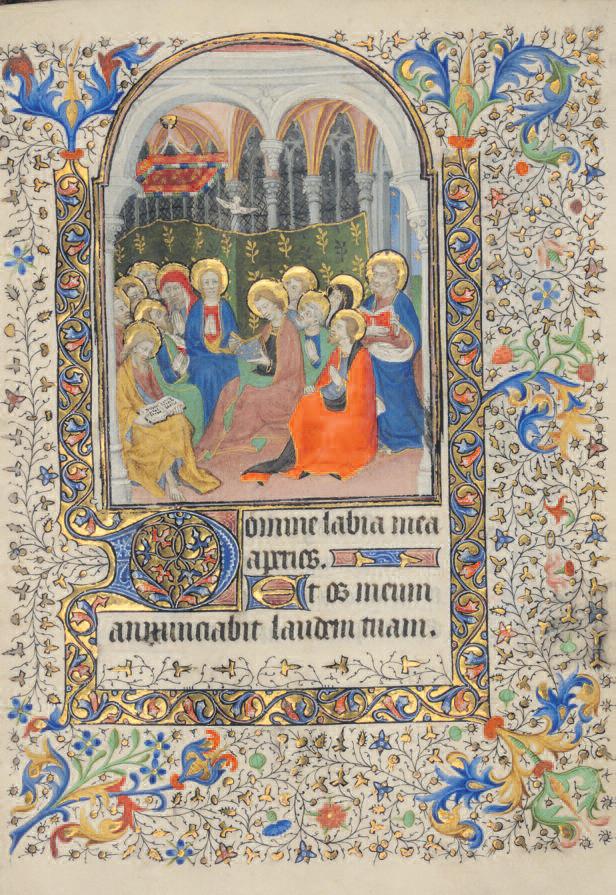

Whalley Abbey testifies to monastic life, in the form of Cistercian monks, during the late Middle Ages. Established in 1296, it had a relatively short life of less than 250 years, before being dissolved by Henry VIII. Despite the bad press that is sometimes meted out, monasteries served as an important cultural driving force, maintaining the art of writing and illuminating manuscripts, generating artistic and architectural trade, and working the land to sustain their communities. If the Cistercian monks were more aesthetic and orientated to a life of prayer, all the more because of their desire to serve God alone.

Although the Shrine at Fernyhalgh pre-dates the Abbey with a devotional history extending back to the 11th century, it speaks most powerfully of the harshest period of the Protestant Reformation and the testimony of the Martyr-saints. The staunch faithfulness of local recusant Catholics, the determination of missionary priests and the willingness of all to lay down their lives for their belief in the one Church established by Jesus Christ, is vividly expressed in the collection of relics and in the famous Burgess Altar. This latter is a beautifully carved wooden altar, complete with a triptych of panels and a Nativity Scene underneath, which closes up to disguise itself as cupboard. Saints Edmund Campion and Edmund Arrowsmith are amongst the many priests to have offered Holy Mass at it, risking their lives and those of their congregation for this greatest of Mysteries.

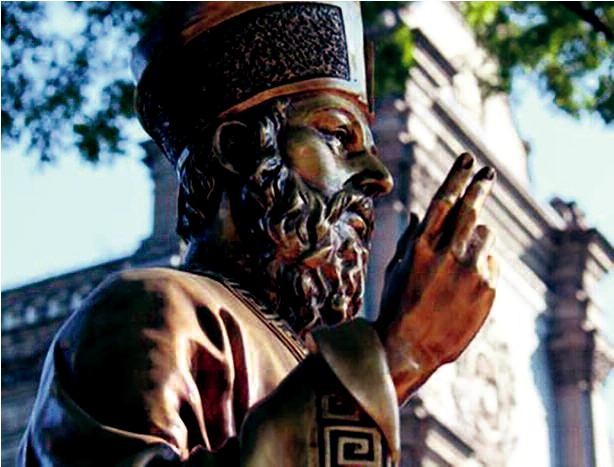

Stonyhurst College of course begins its history precisely because of the Reformation, with the establishment of the school at St Omers in France, in 1593. Its story on English soil starts in 1794. Across both periods however, the school’s story is a testimony to the creativity, ingenuity, learning and sheer hard work of the Jesuit order. The great learnedness of the Society’s members is evidenced in multifarious ways in the school’s operations: the contribution to astronomy through the work of its observatory; the design and operation of its own powerplant; the writing and production of whole series of plays; numerous musical contributions. All of this has its inspiration and final end “ad majorem Dei gloriam” (for the greater glory of God).

Across this panoply of Catholic activity, the underlying dynamic is the same: a personal conviction that God became man, and that He died and rose on the Cross for our salvation. If we wonder at the force of the conviction held by those monks, martyrs and school masters, it is because it was not simply a belief: it was faith. And therein lies a subtle, but substantial, distinction. In a society which tends towards viewing beliefs as a private matter, each as valid as the next, which may be held freely so long as they do not interfere in the lives of others, it is easy to lose a sense of the grandeur of the theological faith that the Church holds.

Beliefs are common to everyone – be they beliefs in a political system or in the wisdom of their favourite TV personality – and indeed everyone has some belief about God. In all its guises however, belief remains an intellectual act that begins and ends with the human individual. As such, it only has its foundations in that same person.

Faith, on the other hand, is a response. It is firstly the acceptance of Truth: the highest and final Truth, which is valid for all people in all places. This Truth is known to be true by the Christian, not because he or she thinks it an attractive thing to believe, but because it comes from God. How do we know it comes from God? Because we choose to believe the corporate witness of the Church: from those first Christians who saw the God-man walk this earth, down to each and every man, woman and child who has testified to that Truth with their lives over the last two millenia.

Such a faith does not remain a personal belief for private consumption: it prompts an obedience (literally, a “listening to” as the Latin roots signifies) and subsequent action. From Abraham taking all his family and possessions to an unknown destination across the Arabian desert, to those parents of the 17th and 18th centuries illicitly sending their sons across the Channel to receive a Catholic education, they all acted on “the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1): they had faith.

We might be tempted to wonder dubiously at our own faith (or indeed, to avoid asking ourselves what might feel like an embarrassing question!). However, Rome was not built in a day, and neither were places such as Whalley Abbey, Ladyewell and Stonyhurst. The real work started with the daily prayer and attentiveness to God of each individual concerned in all of those histories. The places that remain – be they merely the stones of a ruined church or a functioning school – reach back to beyond the external achievements of those Catholics: they bear witness firstly to lives that were centred around God. Without that continued response of faith – an acknowledgement of God, a prayerful listening to His Word, a striving to live out His teachings – there would be nothing for us to marvel at.

Visiting sites such as Fernyhalgh and Stonyhurst, one should therefore see “through” each physical place to the faith of the men and women that built them. They might be of another era and walk of life, but they follow the same Lord Jesus. They are now united with Him in the great “cloud of witnesses” that watches over us, waiting for us to pick up the baton and run the good race in our own time, and so join them in our heavenly destination (cf. Hebrews 12:1).

Stefan Kaminski is the Director of The Christian Heritage Centre