We discussed in our previous post how Mary is the model of the Christian disciple. She constantly said ‘yes’ to God and adhered perfectly to His will. To be a disciple means to follow Jesus and, as Our Lord said Himself, this is achieved through the Cross: “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Matthew 16:24).

Our individual crosses, our sufferings and trials are all joined to Christ’s suffering on the Cross; as St. John Paul II says, our sufferings have a “salvific” power. He continues that it is for “this reason Saint Paul writes: “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake” (Colossians 1:24)”.

The Church’s tradition tells of Mary’s seven great ‘sorrows’ during her earthly life. These are:

1. The prophecy of Simeon (Luke 2:34-35)

2. The flight into Egypt (Matthew 2:13-15)

3. The loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple in Jerusalem (Luke 2:41-52)

4. The meeting on Jesus and Mary on the road to calvary (handed down in Sacred Tradition)

5. The Crucifixion of Jesus (Matthew 27:33-50, Mark 15:22-41, Luke 23:33-49, John 19:16-37)

6. The piercing of the side of Jesus with a lance and his descent from the Cross (John 19:34-38)

7. The burial of Jesus by Joseph of Arimathea (Matthew: 27:57-61, Mark 15: 42-47, Luke 23:50-56, John 19:38-42)

These are all significant events in the life of Jesus and Mary. Beginning with Simeon’s prophecy in the Temple of Jerusalem that Jesus’ life and ministry would be a monumental one, he also adds, addressing Mary directly, that a “sword will pierce through your own soul” (Luke 2:34-35) and it points straight towards the road to the Cross. The sinlessness of Jesus and Mary is no guard against suffering in a word which is fallen.

St. John Paul II refers to Simeon’s prophecy to Mary as a “second Annunciation” which tells “her of the actual historical situation in which the Son is to accomplish his mission, namely, in misunderstanding and sorrow”. He continues, this prophecy “also reveals to her that she will have to live her obedience of faith in suffering, at the side of the suffering Saviour, and that her motherhood will be mysterious and sorrowful”. Jesus’ life and ministry is one filled with sorrow and Mary’s life is intrinsically bound up with the life of Jesus and her suffering has a salvific role to play.

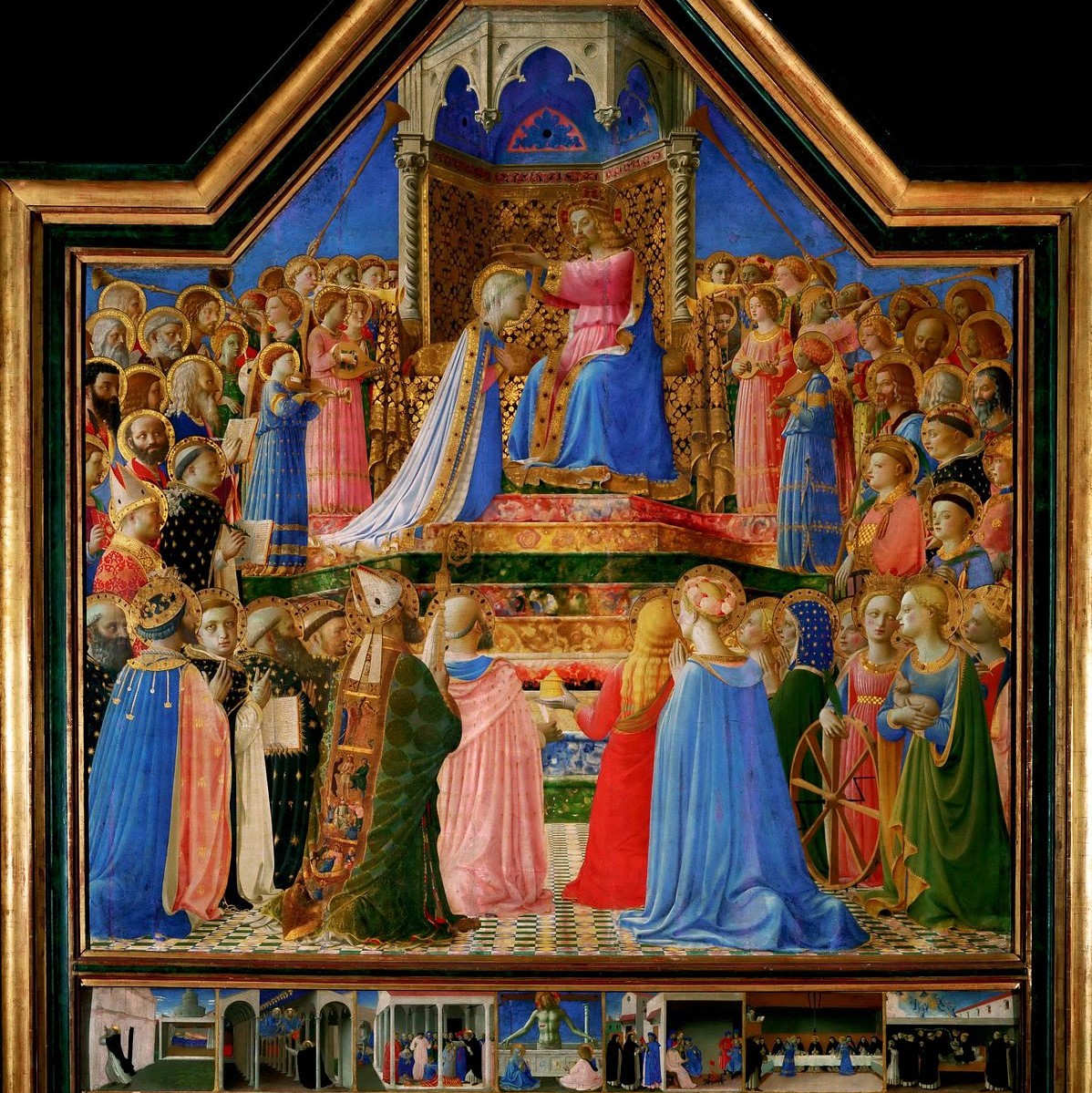

However, we know that the ministry of Jesus does not end in sorrow, but with the Resurrection and Ascension.