Friday 6th July 2018

Stained glass window of a Yorkshire martyr finds a home in Lancashire

Margaret Clitherow provides a fine example of a woman strong in her faith

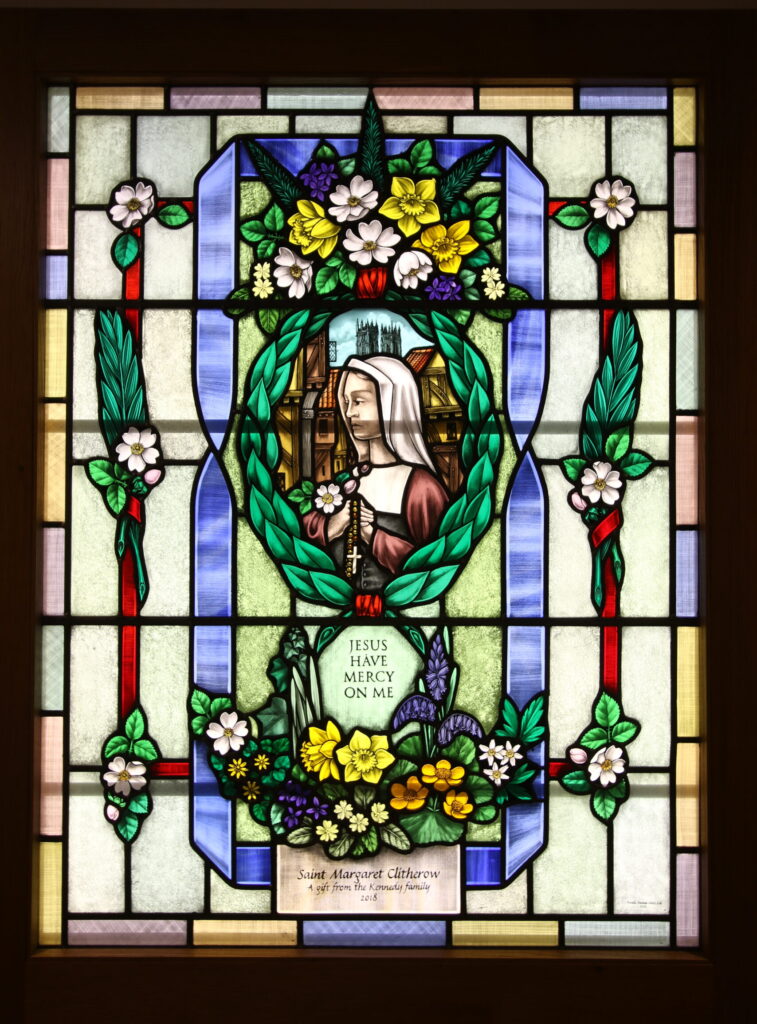

The white rose of Yorkshire will find a special place in the red rose county of Lancashire with a beautiful new piece of stained glass commissioned for Theodore House at the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst, which tells the story of York’s great martyr, St Margaret Clitherow, and recording the memory of her unborn child.

The Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins SJ – who walked and worked in the Stonyhurst grounds of the Christian Heritage Centre and Theodore House – was deeply touched by the story of ‘the Pearl of York’ and left an unfinished poem Margaret Clitherow dedicated to ‘God’s daughter Margaret Clitherow’, paying tribute to her faith and courage in the face of a cruel death.

The new stained glass depicts St Margaret holding an unopened bud of a white rose, representing Margaret’s unborn child, crushed to death with her. It also depicts the Shambles in York, where Margaret lived, and Stydd chapel, near Ribchester, where many believe she was laid to rest in an ancient chapel.

The trustees of the Christian Heritage Centre charity hope this beautiful commission will inspire visitors to celebrate the lives of mothers and their unborn children – particularly in a country where one baby in the womb is aborted every three minutes, 20 every hour, 600 every day. Traditionally and locally made in Padiham, near Burnley, the window is a replica of a piece of work for the Ribchester parish of St Peter and St Paul, near Stydd, and made possible through the generosity of the family of John Kennedy KSG.

On many levels, St Margaret’s story speaks powerfully into our own times. Her practical support and hospitality towards outlawed priests; the tolerance practiced within her own family; her spirituality, courage and fortitude act as a stirring rebuke to our half-heartedness. Canonised in 1970 by Pope Paul VI, Margaret was crushed to death – peine forte et dure – in York, on Good Friday, 25th March 1586, for harbouring Fr Francis Ingleby, a Catholic priest. The York assizes had ordered her to be stripped naked; to be laid on a sharp rock; and for an immense weight of stones and rocks to be placed on a door. This was placed on top of her, crushing the life from her body. After an earlier arrest, her third child, William, had been born in prison. Now pregnant with her fourth child, and aged 30, she was executed on Lady Day. Her body was thrown on a dung heap. Her last words had been “Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, have mercy on me.”

The story has it that six weeks later a group of Catholics recovered the body, embalmed it, and had it taken to a secret place. Margaret’s right hand was removed from her body and is today kept at York’s Bar Convent. The location of her grave is an unsolved mystery but visitors to Theodore House can go to Stydd chapel where many believe she is buried. Stydd is close to the village of Ribchester – a one-time Roman garrison town complete with baths and temple.

In 1789, it was here, before emancipation in 1829, that Catholics built a small barn church, dedicated to St Peter and St Paul. But it is the nearby chapel of St Saviour, with its Saxon origins, and a structure dated to the mid-12th century – and beautifully restored by its Anglican guardians – that holds the clues to the possible whereabouts of St Margaret.

Originally the chapel was part of a small priory of Knights Hospitallers of St John – skilful herbalists and healers, caring for lepers, the sick, and pilgrims. St John’s holy well, aid to have healing waters, is close by. The knights were here for 300 years, until Henry VIII confiscated their houses.

Legend has it that Margaret’s posthumous journey to Stydd began when Fr Francis Ingleby, the priest she took into her home, arranged for her body to be taken west to a relative. Ingleby was related to the Catholic Hawksworth family of Mitton, near Ribchester. Missionary activity in the area was centred on Bailey Hall, in the parish of Mitton and it is believed that Margaret’s body was first taken to Bailey Hall.

But in 1716, after the Catholic Shireburn family supported Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Hall was forfeit and to ensure that the body was not desecrated it is said to have been removed to Stydd. In 1915 some students from Stonyhurst College excavated the ruins of a burial crypt next to the Hall and found the mausoleum empty.

Yorkshire’s Catholic Vavasour family have an oral tradition that Margaret “was taken a horse’s journey at night and was buried; there she will

remain until the Church is restored to its own.” That Catholics held Stydd to be especially holy ground is borne out by the request of Fr Sir Walter Vavasour – a Jesuit whose missionary work was based at Bailey Hall, and who died in 1789 – to be buried there. Two other Catholic priests – Fr Charles Ingolby and Fr Richard Walmsley – made the same request. More intriguing still is the white marble gravestone of Bishop Francis Petre.

It must be unique for a Catholic bishop – and Apostolic Vicar at that – to request burial in what had become an Anglican chapel. The Latin inscription on his tomb translates as follows: ‘Here lies the most Illustrious and Reverend Lord Francis Petre, Of Fithlars, of an illustrious and ancient family in the county of Essex, Bishop of Amoria and Vicar Apostolic of the Northern District; which he governed with discernment and care for 24 years, being its patron and ornament by his kind acts and apostolic virtues;

then full of days and good deeds, after bestowing many alms, he died in the Lord on the 24th December of the year 1775, aged 84. May he rest in peace.’

The other interesting gravestone, dating from 1350, has a lovely floriated design and buried here are the Knight Sir Adam de Cliderow and his wife, Lady Alice Cliderow. Next to Bishop Petre’s grave is a simple cross and it is believed by many that this is where Margaret Clitherow lies. But, regardless of whether this is her final resting place, the Trustees of the Christian Heritage Centre believe her life and death should inspire us today.

Hers is the story of a courageous woman whose family had to make sense of the religious conflicts of the day. A Catholic convert, and married to John, an Anglican, who lovingly stood by her throughout her ordeals. She became renowned for her personal holiness, gaining her strength by praying daily for an hour-and-a-half and fasting four times each week. Her story reminds us of the Christians who suffer persecution, death, and torture on a daily basis all over the world; it speaks about the need to respect difference. It recalls the wanton destruction of innocent unborn life.

On arrest, Margaret refused to plead – since a plea would incriminate her family and her servants and she said that she wished to spare the jury’s conscience. She knew that the penalty for refusing to enter a plea was death by crushing. Her only statement was “Having made no offence, I need no trial.” This, then is a story about conscience – reminding us of the price paid by contemporary women, like the Glasgow midwives who lost their jobs after refusing to be complicit in the taking of the lives of children in the womb.

The new window, and a room, in Theodore House commemorating Margaret Clitherow will be a fitting tribute to a great northern woman. Visitors to The Christian Heritage Centre will take her story to their hearts.