Friday 7th February 2020

A change of Christian climate, and its deniers

Stefan Kaminski

That there is a change in the Earth’s climate is an undisputable fact. The significance of that change is debated by some. Others label these people as ‘climate change deniers’. However, there has also been a different sort of ‘climate change’ going on for a while, which also has its own set of rather vocal deniers.

In last month’s article on Christian heritage, Sr Emanuela Edwards wrote eloquently of the significance of the Magi’s journey. She noted their wisdom and courage in recognising and following the star, which guided them to the full revelation of the Incarnate God.

Her article was a call to Christians today to offer such a “guiding star” to the people of our own times by their witness to the faith. The particular need for visible ‘stars’ in contemporary society was already present in St Pope Paul VI’s time: she noted that he had already identified a “rupture between the Gospel and culture as the drama of our time”.

Christianity has provided the general ‘climate’ for European culture for the best part of the last two millennia. It has shaped the greatest thinkers, writers, artists and scientists who stand unchallenged at the pinnacle of what Europe has to offer. From Augustine to John Paul II, from Agnelli to Pugin, from Albertus Magnus to George Lemaître: they were all formed by a certain worldview, which has gradually been divorced and discarded by modern thinking.

That worldview, which the scholastic thinking of the Medieval period had elaborated and expressed so clearly, understood the entire cosmos as being in an inherent relationship to God. Creation is not seen merely as a onetime, distant event somehow linked to God, who is then subsequently written out of everything that happens since; creation is a continual act of holding everything in being, intentionally guiding every development in the cosmos, however random these may appear to us.

Frank Sheed (of Sheed & Ward publishers), described it as “nothingness worked upon by omnipotence”. Deliciously succinct, this phrase captures the two essential facts about our world, from a Christian point of view: it would not exist if God did not will it; it only continues to exist because God continues to will it.

This is the perspective that underwrote our Western culture, providing direction and impetus for both the sciences and the arts. The meeting of faith and culture was not simply a convenient intertwining of two parallel strands: culture was shaped by faith. Nonetheless, many academics today insist on minimising, if not altogether setting aside, the religious dynamic when delving into the minds of those cultural icons whom we all admire. A bit like today’s climate change deniers (but in reverse), they attempt to write the significance of a previous, Christian climate out of the textbooks.

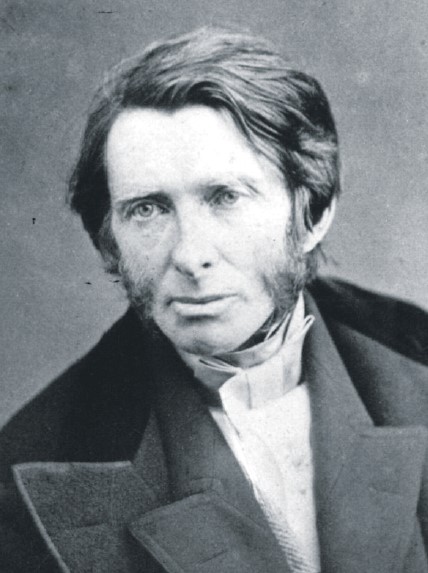

One such icon whose Christian adherence and life is frequently downplayed is the Victorian polymath, John Ruskin. He was the subject of our first evening talk of the year at The Christian Heritage Centre. Professor Keith Hanley, of Lancaster University, offered a fascinating insight into John Ruskin’s Travels on the Continent, providing us with a view of European art through this particular set of English eyes. Brought up as a devout evangelical, Ruskin had clear ideas of what defined good landscape painting. As the epigraph to his five-volume series on modern landscape painting stated, ‘Nature presented the laws behind God’s creation for mankind. Landscapes, therefore, were worthy insofar as they revealed the truth, the beauty and the intelligence of God’s creation.’

In Ruskin’s opinion, the realism of William Turner was the epitome of this artistic form, which formed the comfortable confines of Ruskin’s artistic world for his early years.

But Ruskin’s first solo trip to Italy changed all that. There, he was confronted – and indeed, “utterly crushed”, as he put it – by the revelation of the full ‘Art of Man’. His initial encounter with Jacopo Tintoretto’s work in the School of St Roch, and in particular with Tintoretto’s Crucifixion, opened his eyes to the world of “theological symbolism of the entire Christian scheme of redemption”, as Prof Hanley expressed it. Thereafter, while his views continued to evolve, they were marked by a new and lively sensibility to the transcendent world, which informed and brought a whole new significance to the material order.

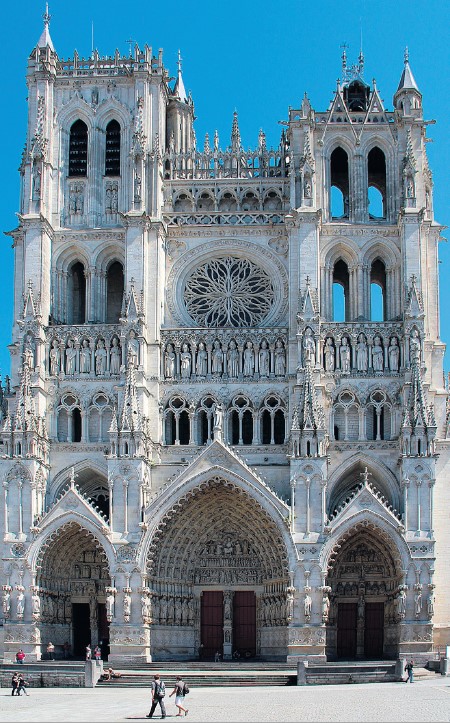

Indeed, his very last work, on the Gothic cathedral of Amiens, recognised the full drama of the medieval worldview that is so wonderfully expressed in the cathedral’s West Front: the interconnectedness of everything, from the lowliest elements of creation to the highest personages in the Judeo-Christian tradition, in a single, allembracing path to Christ.

Our next evening talk at The Christian Heritage Centre, Stonyhurst will pick up another figure who has been recently “rediscovered” and again often remoulded to the post-Christian thinking of today: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. His realism, often considered in purely psychologically terms, has even led some to consider him a 20th century painter in spirit. Yet his genius is firmly grounded in the dynamism between the spiritual and earthly worlds, and his ability to communicate this.

Providing a “guiding star” to the one true Creator and Redeemer of the world in today’s society also requires being able to point to and reclaim the fruits that have been borne by our faith over the course of its history.

There are plenty of voices ready to point out the apparent defects of Christianity and the problems they claim it has caused; we need more voices that can speak eloquently of the truth and beauty that Christianity has engendered over the centuries in our Western culture.

Stefan Kaminski is the Director of the Christian Heritage Centre, Stonyhurst.