Friday 3rd February 2017

Relics reveal rich tapestry of England’s Catholic past

Stonyhurst College cares for a spectacular and rich array of historic vestments in its collections, many of which were smuggled across the Channel to the school during the time it was based in St Omers near Calais, between 1593 and 1762.

Vestments were particularly singled out for destruction in Reformation England. In the eyes of the Elizabethan government, they represented priestly authority and the celebration of the forbidden Mass.

From the onset of the Dissolution of the Monasteries until the late 17th century, vestments in England and Wales were systematically sought out and destroyed by government agents, keen to suppress all signs of Catholic worship. Ironically a good many which survived the reign of Protestant Edward VI and were brought out in the reign of his Catholic half-sister, Mary Tudor, were subsequently seized and destroyed in the reign of Elizabeth I.

There are numerous examples of Catholic families and communities hiding precious pre-Reformation vestments from the searchers, storing them in attics, in hidden compartments and even burying them, in an attempt to preserve them. Very few survived, and many of these were sent abroad for safekeeping, to the English seminaries and Colleges in Rome, Valladolid, Douai and St Omers.

Many pre-Reformation vestments were richly embroidered with the intricate needlework known as opus anglicanum. The embroideries were removed from the chasubles and dalmatics to make them easier to hide and transport abroad. Once at St Omers, they were re-attached to new, rich fabrics and used in the celebration of Mass for the young boys attending the college. They symbolised England’s Catholic past and were a sign of hope for the restoration of the Catholic faith in England in the future.

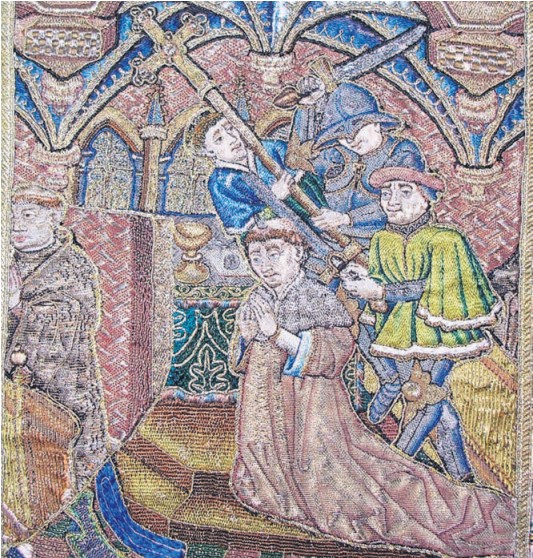

Medieval examples such as the beautiful St Dunstan’s Chasuble survive at Stonyhurst today, smuggled from Canterbury to St Omers, and then brought back to England when the college moved to its present location in 1794. The Dunstan Chasuble is the property of the British Jesuit Province, and is cared for at Stonyhurst. It features highly intricate embroidered 14th century images of saints associated with Canterbury, and probably once adorned a cope, or copes. Thomas Becket features in four scenes, as might be expected for Canterbury’s most famous saint and martyr. The panel depicting his martyrdom is spectacularly fine, and has retained much of its colour and freshness. When these embroideries arrived at St Omers they were re-shaped into their present form on a Roman chasuble, which takes its name from a delightful image of St Dunstan of Canterbury pinching the nose of the devil with tongs.

Another rare medieval chasuble was commissioned in the 1490s by King Henry VII for use in Westminster Abbey. It was originally part of a massively expensive and prestigious matching set of twenty-nine copes, a chasuble, dalmatic and tunicle. These were woven in Florence from cloth of gold and red silk velvet damask, with interloped threads of gold, in a technique known as riccio sopra riccio, or richness upon richness. The design features red rose of the House of Lancaster, the portcullis badge of Henry’s mother, Margaret Beaufort (the Tudor’s main claim to royalty came through Margaret) and embroideries showing the Good Shepherd and angels incensing a monstrance. Of the set (which was taken to the Field of Cloth of Gold by Henry VIII), only two pieces remain; this chasuble and a cope.

Both arrived at St Omers early in its history and were known to have been used in ceremonies at the college as early as 1609.

A poignant reminder of the personal cost paid by Catherine of Aragon for refusing to fall in with her husband’s desire to annul her marriage, can be seen in a set of chasuble, dalmatic and tunicles bearing rich embroidery of grapes and vines. This set is said to have been embroidered by Catherine and her two ladies-in-waiting during her incarceration at Kimbolton in the fifteen months before her death. The set was restored on arrival at St Omers in the late 17th century, and then again in the 1850s, but much of the original embroidery and design remains.

The college also commissioned new chasubles for use in its three chapels. There were many communities of English nuns in the Low Countries in the 17th century, exiled from home because of their faith. It is likely that some of the exquisite Flemish embroideries at Stonyhurst originated in English convents in places like Bruges, Louvain, Antwerp and St Omers. The Lamb Chasuble features rich gold scrolls, laid out like a formal garden parterre, and in between are brilliantly coloured tulips, roses, lilies, violas and honeysuckle, which symbolise different aspects of Mary’s virtues. On the back is a solid panel of silk embroidery with silver and gold thread showing the Lamb of the Apocalypse, lying on the Book with Seven Seals. This chasuble is in remarkably original condition, and is used on special occasions at Stonyhurst.

Missionary priests in 17th century England found it difficult to minister the sacraments to the Catholic communities they visited, as many houses had no place to hide the vessels, books and vestments necessary. It was dangerous for priests to carry these items with them as they were proof that the owner was a priest, which carried the death penalty. Many, however, took that risk as there was no alternative.

In the container known as the Pedlar’s Chest, at Stonyhurst, there is a unique collection of simple vestments made from ladies’ dresses, along with a travelling altar stone, pewter chalice, alb, rosary ring and a quantity of church linen including altar frontals, chalice veils, burses and amices. These were used by priests travelling the Lancashire countryside, visiting remote Catholic farmhouses, manors and hamlets.

The chest itself is made from pine and is covered with ponyskin. The interior is lined with crudely printed wallpaper of hunting scenes. It is exactly the sort of container used by travelling salesmen, or chapmen, using fell ponies over the rough packhorse routes of rural England, and it was this persona that the priests adopted, travelling in disguise.

The packhorse trails had the advantage of bypassing villages with their government-paid ‘watchers’ waiting to interrogate travelling strangers. The paths were rugged and uncomfortable, but they linked Catholic houses, and allowed priests disguised as pedlars to arrive at the back door offering threads and patterns, thimbles and pins. Secret signs and words were exchanged with the lady of the house and the priest was taken to a discreet room to unpack the vestments and celebrate Mass.

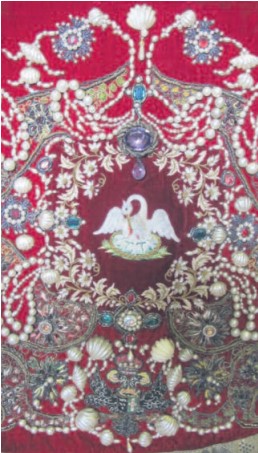

A later vestment tells the story of the changing situation for Catholics in the early 19th century. The Arundell Cope is a sumptuous robe, made from rich, dark red velvet, embroidered with jewels, pearls, gold and silver thread. The velvet was originally used for the coronation robes of James Everard, 10th Baron Arundell of Wardour, who wore them to Westminster Abbey for the crowning of George IV in 1821. His attendance at the coronation was an indication that Catholics were becoming accepted after centuries of exclusion.

There is a final, intriguing item worth looking at. Known as the St Norbert Cope, it has a hood decorated with rich 17th century embroidery showing that saint holding aloft a monstrance. The fabric of the cope is bizarre; deep purple, gold and silver asymmetric designs, fringed with silk and paisley motifs. It was originally the umbrella of an Indian Maharajah’s elephant