Friday 8th January 2018

Fr John chose to die, rather than yield to Protestantism

Br Samuel Burke, OP

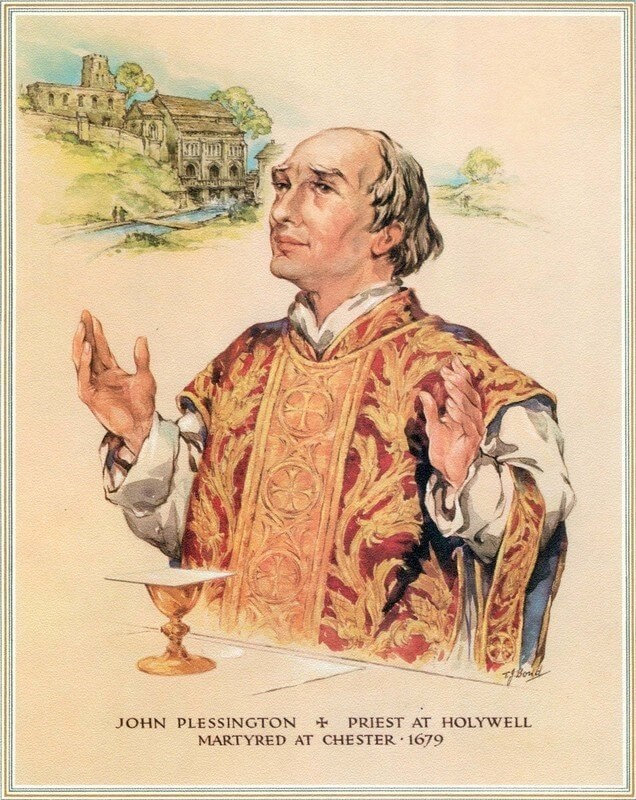

“I am willing to die, and I had rather die than doubt of any point of faith taught by our holy mother, the Roman Catholic Church.” In his ‘last testament’, St John Plessington, a Catholic priest, foretold his own fate.

He died a martyr’s death. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at Gallow’s Hill in Boughton Cross, Cheshire, overlooking the River Dee, on 19th July, 1679. His offence: taking Orders in the Church of Rome and returning to the realm as a Catholic priest contrary to Act 27 of Elizabeth, 1585.

For his troubles, for his fidelity, for his ultimate sacrifice, as Paul VI declared in 1970 along with 39 others, Plessington numbers among the Saints in heaven. But the story doesn’t end there because the question remains: how do we honour the memory of this Saint and others like him?

Our first task is to remember, which is easier said than done. At least in the case of recent Saints, remembering is not a matter of fabled legend, it is an historical exercise, which often requires diligent research. Good, accurate information is important because it bring us closer to the person; they serve to make their memory more real to us; the details matter.

John Plessington was born around 1637, the youngest of three children, at Dimples Hall near Garstang in Lancashire. His father, Robert, was a committed royalist and Governor of Greenhalgh Castle, which stood on a hill overlooking a boggy plain about a quarter of a mile from the family estate. The family were both Royalist and Catholic.

During John’s childhood, Robert fought for the Crown in the Civil War, for which he was later imprisoned and forfeited his property. The Parliamentarians also destroyed Greenhalgh Hall and a lone western tower is all that now remains of the fortress. As Catholics, the family kept a priest and a chapel.

Their chaplain, the Venerable Thomas Whitaker, was captured and martyred in 1646. Perhaps this was one of John’s earliest memories, aged about nine. Did the martyrdom of the family priest inspire his own priesthood and martyrdom?

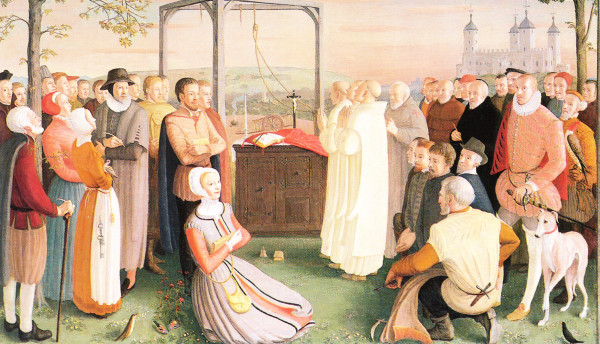

Educated by the Society of Jesus, John left the family home first for Scarisbrick Hall, near Ormskirk, and subsequently leaving Lancashire for St Omers in France, a forerunner to Stonyhurst College. The Jesuits were famed not only as “the schoolmasters of Europe”, they have also been dubbed “the shock troops of the Counter-Reformation”, a glib remark that fails to do justice to valiant mission and unparalleled sacrifice which they made to the Greater Glory of God and for the preservation of the faith in England during penal times.

If our first task was to remember, our second task, I think, is to understand the human context. Part of this is speculative, of course, but we must seek to understand the motivations and challenges that the martyrs faced if we are to appreciate their witness in its fullness.

From France to Spain where John, taking the pseudonym ‘Scarisbrick’ — perhaps in tribute to his early educators — studied at the Royal College of St Alban, Valladolid, along with five other fellow seminarians in November 1660.

As a welcome gesture, they were given a good supply of tobacco to help them settle in. Within a very short time, John was ordained a priest on 25th March in 1662 at Segovia. Not long after, ill-health curtailed his studies and, though a priest, he returned to England with his theological studies incomplete. Little is known about his early ministry in Lancashire. What is known is that he subsequently lived and ministered at the St Winefred’s Shrine at Holywell in North Wales. The area had a strong Catholic community supported by secular priests, including Plessington, based at a local Inn, Ye Cross Keyes, and a Jesuit mission based at another pub, Ye Old Star Inn, a pub which plays another role in Plessington’s tale to which I will return.

Some time before 1670, perhaps as early as 1665, Fr Plessington is to be found at Puddington Hall, home to the Massey family near Burton, on the Wirral. Officially, he was tutor to the Massey children but in reality he was the resident priest, supporting the family and Catholics in the surrounding area. For a brief time, there was relative toleration for Catholics and Fr Plessington would have probably gone about his ministry discretely but without too much trouble. This was not to last.

In 1678 Titus Oates’ feigned to reveal an elaborate conspiracy to assassinate Charles II and replace him with his Catholic brother, James. Catholics, especially priests, were rounded upon by authorities.

They stood accused as conspirators in the ‘Popish Plot’. In all, some 45 Catholics were executed in this wave of persecutions. On the Wirral, directions came from the King’s Ministers in Whitehall for the local authorities to exercise great vigilance and near panic ensued.

It seems that Fr Plessington was targeted following the report of a Protestant landowner who was grieved at the refusal of a match between his son and a Catholic heiress. It was presumably on the basis that a Protestant husband would be unwilling to risk keeping a priest, and, as a consequence, such matches would inevitably result in the falling away from Church.

On 28th December 1678, the priest hunter Thomas Dutton raided the house at Puddington and, despite the house having a priest hole by the chimney, Fr Plessington was found and taken into custody. Dutton received a handsome reward of £20 for his troubles.

The trial of Plessington, which followed was defective in several respects. Three lapsed Catholics testified against him but their evidence was seemingly insufficient. The first witness was deranged, as confirmed by her father and neighbours, and the second Fr Plessington had never met. This left only a third valid witness, a man named Robert Wood.

However, for a capital offence, at least two witnesses were required for a conviction, as Fr Plessington pleaded in the court. Nevertheless, the jury still convicted him. Such was the ill-feeling at the conviction that the judge granted a reprieve only to have this overturned by Whitehall.

Though awaiting death for nine weeks in a damp underground cell at Chester gaol, Fr Plessington maintained a lively sense of humour. When his friend, Sir James Poole visited him at the same time as an undertaker who was apparently measuring him for a coffin, Fr Plessington joked that he was giving orders for his last suit!

Dragged on a hurdle through the city of Chester from the Castle to Gallow’s Hill, overlooking the River Dee, Fr Plessington was hanged, drawn and quartered on 19th July 1679. His body was later committed to Puddington Hall, where it was ordered that the body parts be displayed on the four corners of the property. In open defiance of this charge, the Massey family laid out Plessington’s dismembered body on an oak table.

Where the martyr’s remains are is a matter of some debate. 140 years after Plessington’s death, a collection of bones bearing fractures consistent with his death, wrapped in children’s clothes of the period were discovered in a trunk in Ye Olde Star Inn. There is good, albeit circumstantial, evidence to suggest these are the bones of St. John Plessington.

A few years ago, an appeal was made by the Bishop of Shrewsbury to conduct DNA tests on the bones. Let us hope that will happen soon so we can honour the relics and memory of this martyr.

This brings me finally to our third task in honouring the martyrs: learning the lessons of history. It is to this third task especially that the new Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst is committed.

This special museum is housed at the very school at which Plessington was educated, no longer in exile on the continent but in his native Lancashire. We will strive not simply to retell his story, important though that is, and not only to understand the human context, but crucially to ask also what lessons we can draw from the witness of martyrdom, even as they are made today.

Bloodshed, oppression and discrimination against Christians takes place the world over. One thinks particularly of the genocide of Christians in the Middle East.

There is much to learn from the life and death of St John Plessington about the importance of Catholic education; the mentality of the mob and scare-mongering; about the importance of legal process; about maintaining a sense of humour in the face of adversity; about faith and, yes, about Christian heroism – if we can learn some of that, we will have truly honoured the memory of the martyrs.

Br Samuel Burke, OP, is a Trustee of the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst.