Friday 8th June 2018

The witness of St Edmund Campion: a heroic story of faith

Graham Hutton

Last month we thought about the martyrs for the faith associated with the Tower of London, all of whom suffered under Henry VIII and who will be commemorated by the Christian Heritage Centre when Theodore House opens at the end of the summer.

Sadly, as the story of St Edmund Campion reminds us – and whose life and death has so many associations with our project – in the reign of Elizabeth I, the Tower would once again be adorned with the presence of many confessors for Christ, most of whom paid the supreme penalty.

The first of these was Blessed John Felton, imprisoned and tortured on the rack three times before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn for having affixed a copy of Pope St Pius V’s Bull of excommunication of Elizabeth, Regnans in Excelsis, to the gates of the Bishop of London’s palace near St Paul’s Cathedral. Others included St Ralph Sherwin, Protomartyr of the English College, also racked in the Tower and then executed at Tyburn, and St Philip Howard, who left an inscription on the wall of his cell in the Beauchamp Tower which reads ‘The more suffering with Christ in this world, the more glory with Christ in the next’.

Of all these glorious martyrs, however, the one who is closest to the heart of the CHC is St Edmund Campion. When in 1564 Queen Elizabeth visited Oxford University, where Campion was a fellow, his learning was such that he was chosen to give a Latin oration in praise of the Queen. His oration won great praise and earned him powerful patronage at Court. Ordained as a deacon in the Church of England he would undoubtedly have risen to high office in that Church had he not gradually became convinced by the claims of the Catholic Church.

This led him to renounce the brilliant career which lay ahead of him and to leave England for the continent where he was reconciled with the Church of Rome.

At first he studied at Douai but in 1573 left for Rome to join the Society of Jesus. It was quickly decided that he should join the Austrian Province

of the Society and in 1573 he travelled first to Vienna and then on to Brunn and finally to Prague where he remained for six years. Here he was Professor of Rhetoric and Philosophy and Latin preacher. In 1580 it was decided that the Society of Jesus which, until then, had provided no priest for the mission to England, would send two, and Campion was chosen to be one of them. He returned first to Rome and from there made his way through France with Robert Persons, and a lay brother, to St Omer. On 24th June 1580 Campion set foot in England for the first time in nine years; he knew that he was returning to almost certain death.

Campion’s mission was to the Catholics of England. It was now 21 years since the second break with Rome and few of the old priests ordained under Queen Mary I remained alive. The Mass had been proscribed by a law which imposed a fine of 100 marks and 12 months’ imprisonment for the hearing of it in addition to the large fines which were imposed on so-called recusants for failing to attend the services of the state Church.

Nevertheless, many remained loyal to the Church, and Catholicism was particularly strong in some of the great aristocratic households of the Thames Valley and the Sacred County of Lancashire. It was to these houses, with their secret Catholic chapels and holes in which the sacred vessels and vestments (as well as the priests themselves in time of emergency) could be hidden, that Campion went to minister. In disguise he travelled extensively ‘through the most part of the shires of England’ (Persons) hearing confessions and saying Mass for the faithful who would have had no access to the sacraments for many years and yet who had kept faith.

During this time Campion wrote Decem Rationes defending the claims of the Church against those of the state church. This document was widely circulated and led to an increase in the government’s

determination to track down Campion. Betrayed by a spy at one of the Catholic houses, Lyford Grange in Berkshire, and after an extensive search of the house, he was found lying in one of the secret priest’s holes.

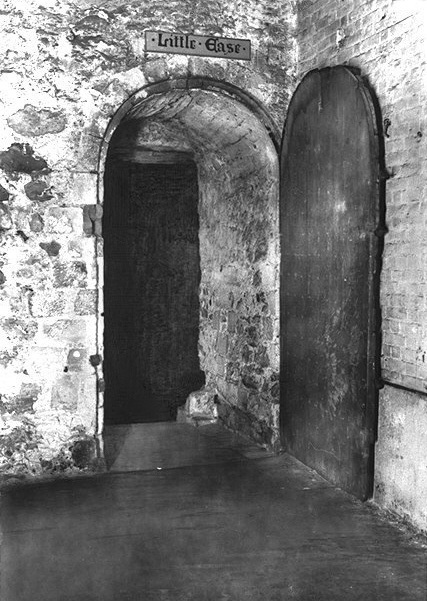

Campion was, of course, taken at once to the Tower where he was initially imprisoned in the cell known as the Little Ease because it was so small that a man could neither stand upright not lie down in it. Here he had to crouch in the halflight for four days before he was taken out for examination by senior officials of the Crown. He was then promised that even now he could obtain freedom and great preferment if he would renounce the Church of Rome and return to the state Church. Campion, of course, refused and was returned to the Tower where those who had offered him his freedom now authorised his being put to the torture.

For three months Campion suffered intermittent torture on the rack. By the time he came to trial in November he was so physically broken that he was not even able to raise his right hand to take the oath. At the trial he was found guilty of treason and condemned to the usual barbaric form of execution. On hearing the dreadful sentence he and the other priests condemned with him burst into singing the Te Deum.

Despite his broken body, Campion was now forced to take part in a series of disputations in the Tower in St Peter ad Vincula. Despite the disadvantages, Campion acquitted himself well and put up a strong defence of his faith.

On 1st December St Edmund Campion along with two other priests met at the Coldharbour

Tower. It was raining as it had been for several days and the London streets were foul with mud. The three priests were bound on hurdles (as was customary) and dragged by horses for several miles through the muddy streets from the Tower to Tyburn. The rope with which he was bound is held in the Collections at Stonyhurst.

One witness records how one gentleman along the way wiped Campion’s face ‘all spattered with mire and dirt’. At Tyburn St Edmund made a brief speech before being hanged, drawn and quartered. Standing near the front of the enormous crowd was Henry Walpole. He came of a Catholic family but had fallen into indifference. Now, when St Edmund’s entrails were torn out by the executioner, a spot of the martyr’s blood splashed his coat. In that moment he was converted and immediately afterwards left England, became a priest and 13 years later suffered the same martyrdom as St Edmund, although in his case at York rather than Tyburn.

Why do stories like this matter? It’s because they remind us of the price paid for the religious freedoms that we enjoy today and the central importance of upholding the right of every man and woman to believe, not to believe, or to change their belief. In promoting freedom of religion

and belief, The Christian Heritage Centre will shine a light on today’s Towers and today’s tortures – from Eritrea to Nigeria, from North Korea to Pakistan.

Graham Hutton is a Trustee of the CHC and Chairman of Aid to the Church In Need.