23rd April 2021

St George, the Martyr-Knight

Stefan Kaminski

Celebrating our martyr-patron, St George, necessarily involves some distinguishing of fact from fiction. Even some of the earliest narratives from the 5th-century that relate to St George claim some rather incredible stories of him. We automatically associate him with a dragon, but ironically this story can’t be traced further back than the Golden Legend of the 12th century.

What is clear is that the St George did exist as a historical person. An ancient cult, and the accounts of several pilgrims in the 6th to 8th centuries, all speak of Lydda as the resting-place of his remains and of the veneration which had been accorded him since his death in about 303 AD. His martyrdom would have therefore occurred under the tyrant-Emperor Diocletian, who was also sometimes allegorised as a dragon – one possible explanation for the associated story.

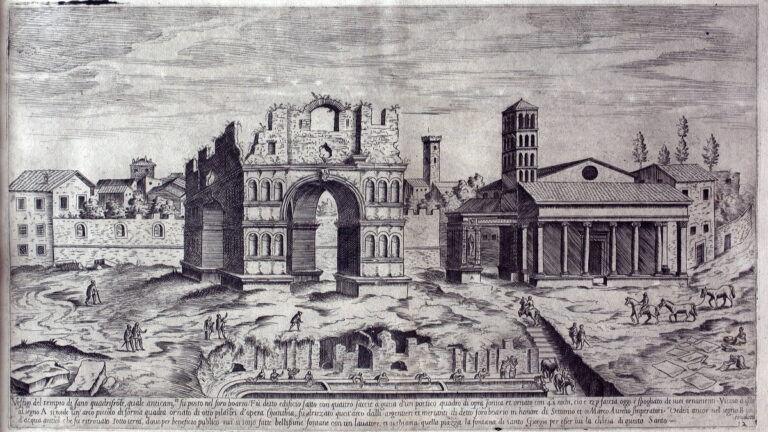

The veneration of St George spread quickly in both East and West. A church in Rome was already dedicated to him by 512AD, and it still stands today. His cult was “exported” to England by the 8th century, and churches had been dedicated to him by the time of the Norman conquest.

The crusades brought about an increase in the popularity of such “martyr-knights” as St George, whose patronage was invoked to support righteous causes. George was particularly seen to personify the ideals of Christian chivalry, and so was quickly adopted as a patron of various city states and countries. King Richard the Lionheart is said to have been responsible for introducing St George’s coat of arms. However, by 1222 his feast had already been proclaimed a holiday. By the 14th century, English soldiers were bearing St George’s coat of arms, but the official seal of Lyme Regis already consisted of a ship bearing the “George cross” in 1284. His cross remains the British Navy’s ensign today.