Contemplating Corpus Christi with Raphael

Dr Joey Belleza

The Solemnity of Corpus Christi – and moreover the 760th anniversary of its institution, celebrated today in many countries and in the UK this Sunday – is, as ever, an occasion to take up with joy that interior pilgrimage from human reason to divine faith, in the contemplation of the Eucharistic Lord.

The centrality of this tremendous and beautiful mystery to our Catholic Faith, as the Second Vatican Council was at pains to underscore, is no less true now than it was when Pope Urban IV instituted the solemnity in 1264.

Indeed, today’s world is in particular need of concrete and visible reminders of the sacred. The expression we give to our Eucharistic faith in our liturgies, in our processions, in our artistic endeavours is a witness to Christ himself.

The solemnity of Corpus Christi is an opportunity to express our inexhaustible desire to do everything we can to honour the Incarnate Word in, as Saint Thomas wrote, corda, voces, et opera: [in] our hearts, voices and deeds.

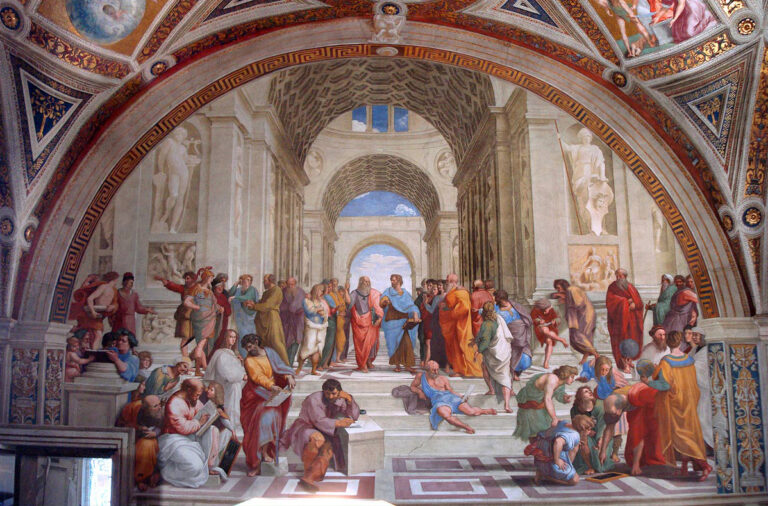

Set against this background, Raphael Sanzio’s Stanza della Signatura in the Vatican, with its two frescoes of The School of Athens and The Disputation on the Sacrament, offers a rich context for philosophical and theological reflection.

In the School, a host of ancient philosophers surround the central figures of Plato and Aristotle, who walk along the central path. Plato’s upward index finger contrasts with Aristotle’s outstretched and downward facing hand, the former gesturing to the truth of eternal Forms, the latter appealing to the reality of the sensible world.

Raphael places them centrally and side-by-side, neither overtaking the other, both sharing a joint if incomplete priority in the philosophic pantheon. The central vanishing point of the fresco – where their gazes meet – is not simply the midpoint between the two, but looks toward an ever-present “beyond” lying ahead.

This central confrontation between Platonic idealism and Aristotelian realism, however, leads not to an unresolved tension, but to an implicit yet powerful conclusion, for directly across the stanza, on the corresponding point in the Disputation – opposite the point between the faces of Plato and Aristotle – Raphael places the Blessed Sacrament.

The host containing the presence of the Incarnate Word is found within the dialectical exchange between the two great philosophers, such that Christ himself – specifically the Eucharistic Christ – is the vanishing point on which philosophical knowledge must converge.

On the one hand, the philosophical enterprise shown in the School and epitomised in the joint pilgrimage of Plato and Aristotle, has its own beauty and purpose. The other philosophers surrounding them, likewise striving toward the truth, are not mere ambassadors of error but important signposts on the way to the fulness of wisdom.

Even Thomas Aquinas, one of whose best-known contributions is a series of “proofs” for God’s existence, understood that philosophy indeed grasps something of the highest truth – the existence of a God above all being – through its own methods, without the explicit aid of grace. But, he admits, of this God we can know very little. Whether he saves us or acts in history or takes flesh is beyond the purview of mere reason.

For this reason, Raphael depicts the School indoors – some say in a building resembling the unfinished “new” Basilica of Saint Peter – as if to emphasise that philosophy has a ceiling, or that its highest aspiration can only be that of a church under construction. And the God of this church remains as impersonal and un-concrete as the space between Plato and Aristotle.

And yet, significantly, their gaze is also half-turned to the opposite wall where the Blessed Sacrament stands on an altar, surrounded not by pagan philosophers but by bishops and Doctors of the Church.

Above the monstrance, the risen Christ is seated in glory and is flanked by the great figures of Scripture. The hand gestures of the several Saints and Doctors mirror both the upward gesture of Plato (this time pointing to Christ in heaven) as well as the downward palm of Aristotle (here pointing to Christ in the sacramental species).

In a sense, the dialectic between idealism and realism is not abandoned in the theological vision of the Disputation; rather the operations of philosophy are taken up and elevated into the realm of faith and theology, such that what appears to be a confrontation in philosophy is brought to a synthesis in theology.

And this unity of the two disciplines – of natural reason and supernatural faith – is joined together in the little host which contains the Incarnate Word himself. The School and Disputation, taken together, convey how the Eucharistic liturgy is “the summit to which all the Church’s work is directed” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 10). It is a summit which has no ceiling but reaches upward toward the enthroned Christ in heaven.

The Eucharist is also the “font from which all the Church’s power flows” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 10). The outpouring of this power, celebrated in a truly Eucharistic way of life, generates a vibrant Christian culture, expressed in art, architecture, and music that can stir hearts to devotion and love of the Creator, and which can assist others in making the interior pilgrimage from reason alone to reason-with-faith.

As Raphael shows us, the treasury of sacred art is one concrete example of the ways in which people offer back to God the gifts of his own creation, just as the Eucharist itself is offered, as the Roman Canon says, “from the gifts which [God] has given us”. Raphael’s own work, imbued with a deep sacramental sensibility, is but one example of the splendour of sacred art rooted in devotion to the Eucharist.

This splendour is also seen in the many little processions happening in parishes and communities all over the world to mark the Solemnity of Corpus Christi.

The colourful floral displays covering the streets in Spain, Italy and Portugal; the wealth of sacred music composed for this feast; the Eucharistic verses of Aquinas himself, monuments of medieval Latin poetry; and of course, the processions which mark this great Solemnity – all these are manifestations of that same interior pilgrimage toward an ever-increasing faith in the Lord who, as the Collect of the feast says, “left us under this Sacrament a memorial of the passion”.

Of course, one need not be a Renaissance master to express one’s faith in the Eucharistic Christ; one only need to heed Saint Thomas’s admonition in Lauda Sion, the sequence prescribed for the Mass to celebrate the Feast of Corpus Christi: quantum potes, tamtum aude – “dare to do as much as you can”.