Friday 3rd March 2017

Relics of how brave Catholic missionaries cracked China

‘The desire for God is written in the human heart, because man is created by God and for God; and God never ceases to draw man to himself…. In many ways, throughout history down to the present day, men have given expression to their quest for God in their religious beliefs and behaviour: in their prayers, sacrifices, ritual, meditations, and so forth.

‘These forms of religious expression, despite the ambiguities they often bring with them, are so universal that one may well call man a religious being.’

This quote, from the Catechism of the Catholic Church on the Vatican’s website, underpins the selection of astronomical artefacts in this article. These artefacts span different religions and cultures. The collections at Stonyhurst include some remarkable scientific artefacts, reminders of the significant role played in astronomy by Jesuits in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Some, such as the Viatorium, were part of a missionary enterprise by the Jesuits, whose scientific expertise gained for them access to regions and countries which would otherwise be forbidden territory.

The Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst exists to provide a suitable setting for the rare and significant collections which the college has acquired over the centuries. Through careful, scholarly interpretation and explanation, these objects have a vital role to play in the education and illumination of all who come into contact with them.

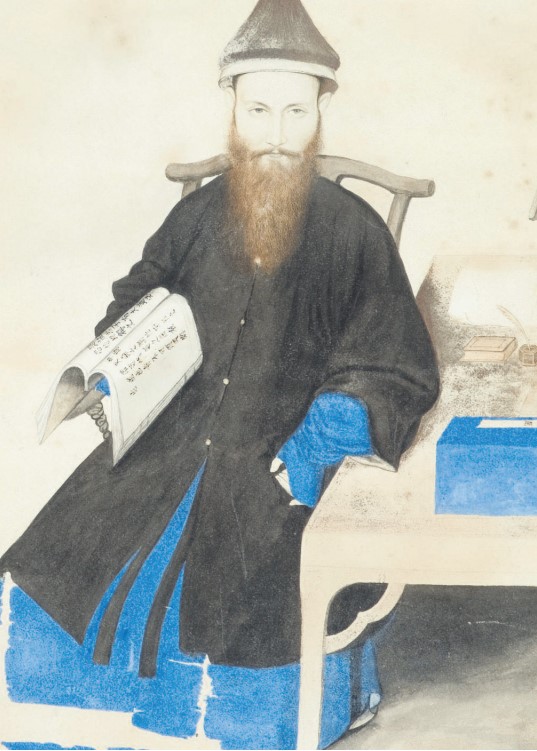

The watercolour of Fr Matteo Ricci SJ was made by Charles Weld, a pupil of Stonyhurst College in the early nineteenth century. He spent much time in Rome from 1845 to 1850 copying paintings of significance to the Jesuit order. An inscription by Charles Weld at the bottom of the paper records that the original painting hangs in the Museo Borgiano at the Collegio Propaganda Fide in Rome. It is assumed that the original painting was by a Jesuit lay brother living in China with Matteo Ricci.

China in the 1550s was a self contained world with its own distinctive ancient culture. Since the eighth century, Christian missionaries had been trying to gain a foothold there without any real success.

In 1552 St Francis Xavier died in sight of mainland China, without ever setting foot on Chinese soil. That same year, Matteo Ricci was born in Italy. He became a Jesuit at the age of nineteen and in 1582, he arrived as a missionary in China. Ricci was highly educated, having studied mathematics, astronomy, literature, philosophy and mechanics.

He reported back to his superiors: ‘I have applied myself to the Chinese tongue and can assure your reverence that it is a different thing from German or Greek … the spoken tongue is prey to so many ambiguities that many sounds mean more than a thousand things … As to the alphabet, it is a thing one would not believe in had one not seen and tried it as I have.’

Ricci quickly adopted the dress and habits of the people around him, and became fluent in Mandarin. His intellect and wisdom earned him great respect in China, and it was his scientific expertise that finally won him an invitation to Peking (now called Beijing) from the Ming emperor, Wan-li (1573-1620), who heard about his collection of European clocks.

The emperor was greatly impressed with Ricci’s learning and kept him at court for 10 years, never actually meeting him, but his favour opened to the Jesuit the doors to Chinese society. Ricci lectured widely on physics, philosophy and Western science, attracting thousands to hear him.

He died at the height of his fame in 1610, fully aware that he had achieved little in the way of converts to Christianity but hoping that he had prepared the way for subsequent missionaries to build on his reputation. His epitaph read: ‘The man from the distant west, renowned judge, author of famous books.’ More than a thousand Jesuit missionaries were to follow him to China in the hundred years after his death. One such was Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a German Jesuit astronomer from Cologne who was sent to Peking as a missionary in 1622. Schall was noticed by the emperor of China, Zhu Youjian, through his faultless predictions of the timings of two lunar eclipses. He wanted permission to preach Christianity but he needed the emperor’s approval

As a test of his scientific skill, in 1627 the emperor ordered him to reform the Chinese calendar which was based on the movements of the constellations, and which over many centuries had become unreliable through inaccurate astronomical observations. Fr Schall worked on the project until 1635, and the recalibrated calendar earned him great fame and respect, as well as the all-important permission to carry out his evangelising work.

Schall was a respected and honoured scholar at the Chinese court, but on the death of Zhu Youjian in 1644, he was thrown into prison and condemned to death.

He was saved by a severe earthquake in Beijing which was seen as a judgement on the sentence on such a notable scholar. He was released from prison and spent the last year of his life in the capital, dying in 1666.

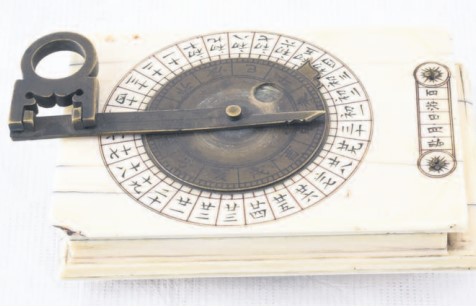

The Viatorium was used for astronomical and surveying tasks. The case carries an inscription with Fr Schall’s name and the date 1638. The lid has characters which translate as Sun and Moon dial for a hundred wanderings.

The circular brass plate on the lid shows the phases of the moon, and the twelve two-hour periods into which the Chinese day was divided. The dial shows the days of the month and the twenty-four solar periods of the year. Inside the box is a space which once contained a compass and a Chinese proverb advising the reader to be aware of the fleeting passage of time and of the need to use it wisely

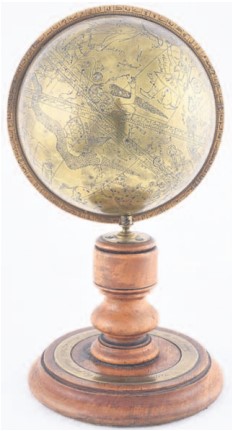

The college possesses a celestial globe made for Islamic scientists. This brass globe, which maps out the heavens for astronomers, is the eleventh oldest Islamic globe known to exist.

It was made in India at the court of the great Mughal emperor, Jahangir (1569-1627), whose son, Shah Jehan (1592-1666), built the Taj Mahal. Jahangir was a cultured man, keen on science, who welcomed western scholars and scientists, particularly Jesuit astronomers, to his court.

The globe is inscribed ‘Qaim Muhammed ibn Isa ibn Allahdad Asturlabi Lahuri Humayuni’ and is dated 1623.

Qaim Muhammed was an astrolabe maker in Lahore, part of a remarkable family which had produced fine quality astronomical instruments for four generations. Their family firm was renowned for its celestial globes such as this one. The globe is seamless, made by a process known as the lost wax method, also used by western Renaissance sculptors. It seems likely that the highly prestigious and expensive globe was commissioned by Itiqad Khan, the brother of Jahangir’s wife, Nur Jahan.

The principal stars of the heavens are indicated by silver dots inlaid into the brass and arranged in Islamicate zodiac form. The circle of the sun’s path is clearly marked, as are the lines that divide the sphere into celestial longitude and latitude. The globe shows all the visible stars and the forty-eight constellations listed by the ancient astronomers such as Ptolemy. It is constructed in such a way that the observer has to imagine that he is placed in the heavens looking down on the constellations, while the earth is hidden inside the globe.

The faith of Islam requires its followers to pray five times a day at specified positions of the sun, and facing Mecca. Using spheres such as this one, in conjunction with other instruments, astronomers were able to use the stars to pinpoint the correct location of Mecca and the exact times for prayer.

The importance of dates and times for Islamic prayer was also the reason for the creation of a small, beautifully illuminated Persian manuscript, which intermingles mathematical tables, with prayers and instructions for ritual washing.

As the Catholic catechism acknowledges, man has historically sought the meaning of his own existence, and wondered at the glory of the heavens, using his God-given intelligence and ingenuity to try and puzzle out the laws of the Universe.