Friday 7th April 2017

‘The road goes ever on and on down from the door where it began ... ’

David Alton

The Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst, in Lancashire’s beautiful Ribble Valley, is a treasure trove of artefacts and memorabilia associated with so many chapters of Britain’s rich Christian story. It is home to over 60,000 objects and 50,000 books, including a Shakespeare folio and manuscripts of the Bard’s relative, the Jesuit poet, St Robert Southwell.

Mark Thompson – a former Director General of the BBC, now editor of the New York Times – who has contributed to the creation of the Christian Heritage Centre, says that the restored historic libraries were a major source of inspiration for his desire to go into journalism: “You read something like Inversnaid and it really brings the texture of that landscape to life. “You’re really lucky to live in that part of the world. You have a feeling that this is a special, unspoilt place. It’s amazing.”

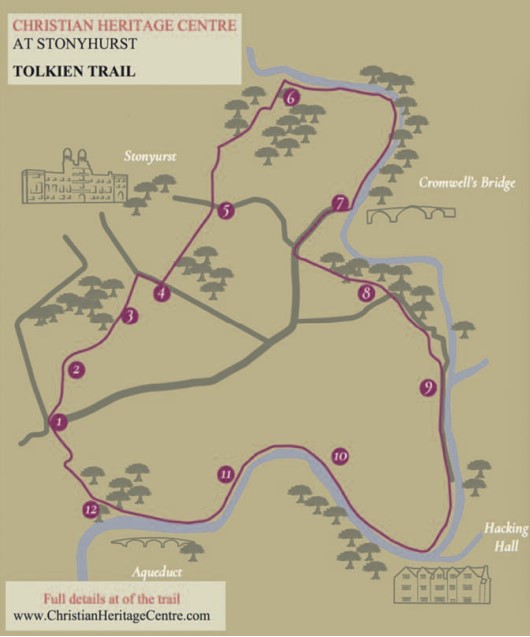

In the Victorian era another young man, Arthur Conan Doyle, honed his writing skills in this same environment while today the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst is promoting a special connection with two of the Catholic world’s most influential writers – the author J.R.R.Tolkien and the poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins. To help visitors get closer to these two men and to understand their Catholic faith, the CHC is making available two wonderful walking trails – guaranteed to inspire.

The author of Lord of the Rings – one of the world’s top ten best-selling books – was a regular visitor to this beautiful part of Lancashire, the sacred county, when one of his sons, Michael, was a teacher at the college, and another, John, trained there for the priesthood (while the English College in Rome was closed during the Second World War). Tolkien’s name appears in the college visitors’ book many times, along with that of his wife, daughter and sons. Since 1954, 150 million copies of Lord of the Rings have influenced vast numbers of readers. Less well known was the contribution he made in 1966 to the Jerusalem Bible – translating the little Book of Jonah. With his friend, C.S.Lewis, and the other ‘Inklings’ Tollkien used his amazing skills as a storyteller to open our eyes to the only story that really matters.

Tolkien was the son of a widowed Catholic convert – Mabel – whose family rejected her when she became a Catholic. On Mabel’s death in 1904, at the age of 34, a death “hastened by the persecution of her faith”, as Tolkien remarked in 1941, he was shunted between relatives until a lodging was found for him by an Oratorian priest, Fr Francis Morgan, who became his legal guardian.

In 1963 Tolkien wrote about the effect that these experiences and formative years had on him: ‘I witnessed (half comprehending) the heroic sufferings and early death in extreme poverty of my mother who brought me into the Church.’ His great closeness and devotion to Mary, the Mother of God – began with the premature death of his own mother. He said that Mary ‘refined so much of our gross manly natures and emotions as well as warming and colouring our hard, bitter, religion.’

Of Fr Francis he wrote: ‘I first learnt charity and forgiveness from him’ and he said that he taught him the story of his Faith ‘piercing even the ‘liberal’ darkness of which I came, knowing more about ‘Bloody Mary’ than the Mother of Jesus – who was never mentioned except as an object of wicked worship by the Romanists.

In a letter to Fr. Robert Murray SJ, Tolkien said of the Virgin Mary ‘Our Lady, upon which all my own small perceptions of beauty, both in majesty and simplicity is founded’. Elsewhere he had said: “I attribute whatever there is of beauty and goodness in my work to the Holy Mother of God.” Tolkien saw Mary as the closest of all beings to Christ, as literally “full of grace” describing her as “unstained” and that “she had committed no evil deeds”. He saw her as the Christ bearer who paves the way for the Incarnation: about which he says “the Incarnation of God is an infinitely greater thing than anything I would dare to write.”

He would have particularly loved the Lady Statue, erected in 1882, that commands the entry to the Avenue and which leads the walker from the village of Hurst Green into the college grounds. Tolkien attended Mass in the now beautifully restored church of St.Peter – and cultivated his great love of the Blessed Sacrament and nurtured his belief in regularly receiving Holy Communion: “I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning and by the mercy of God never have fallen out again.”

He told his son, Michael, that: “The only cure for sagging or fainting faith is Communion….frequency is of the highest effect.”

He described the Holy Eucharist as “the one great thing to love on earth” and that in “the Blessed Sacrament you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity and the true way of all your loves on earth, and more than that….eternal endurance which every man’s heart desires.”

The Blessed Sacrament appears in Lord of the Rings as the lembas, the mystical bread – the bread of angels – which both nourishes and heals. Lembas, we are told, “had a potency that increased as travellers relied on it alone, and did not mingle it with other goods. It fed the will, and it gave strength to endure.”

That Tolkien’s faith was based on personal encounter with God and a deep spirituality is revealed in an exchange that he had with a stranger (whom he identified with his wizard, Gandalf) and who said to him: “Of course, you don’t suppose, do you, that you wrote all that book yourself?” Tolkien replied “Pure Gandalf!…I think I said, ‘No, I don’t suppose so any longer.’

I have never since been able to suppose so. An alarming conclusion for an old philologist to draw concerning his private amusement. But not one that should puff up anyone who

considers the imperfections of ‘chosen instruments’, and indeed what sometimes seems their lamentable unfitness for the purpose.”

Tolkien tells us that: “Lord of The Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously at first, but consciously in the revision”. Elsewhere he states: “I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories), and in fact a Roman Catholic”. In 1958 he wrote that the Lord of the Rings is ‘a tale, which is built on or out of certain ‘religious’ ideas, but is not an allegory of them.’

In 1956 in a letter to Amy Ronald he wrote: “I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a long defeat – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.”

And the Lord of the Rings is full of those glimpses and riddled with wisdom and common sense about everything from the constant battle against evil and the overcoming of seemingly impossible odds, to the nature of friendship to the place of courage: “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

“I don’t know half of you half as well as I should like; and I like less than half of you half as well as you deserve.”

“It’s the job that’s never started as takes longest to finish.”

“Still round the corner there may wait, a new road or a secret gate.”

“Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens.”

“It’s a dangerous business going out your front door.”

“Courage is found in unlikely places.”

But central must be an understanding of power and evil represented by the Ring itself: “The board is set, the pieces are moving. We come to it at least, the great battle of our time.” Principal among those who would face the great battle were Tolkien’s Hobbits – the people of the Shire – and the Christian Heritage Centre at Stonyhurst’s walking trail enables walkers to experience some of the stunning local landscape that, during Tolkien’s visits, would have inspired him.

Appropriately enough, the village of Hurst Green boasts its own Shire Lane while Ribblesdale and Rivensdale seem, at times, interchangeable. The verdant countryside is dominated by the dark shape of Pendle Hill, famous for its association with witches, sorcery and black magic in the 16th century. Inspiration here for Mordor, the Middle Earth’s Misty Mountains and The Lonely Mountain?

And on completion of the ‘Tolkien Trail’ where better to quench your thirst than at the Shireburn, named for the Catholic family who built Stonyhurst:

‘Ho! Ho! Ho! To the bottle I go To heal my heart and drown my woe Rain may fall, and wind may blow And many miles be still to go But under a tall tree will I lie And let the clouds go sailing by’