29 December 2023

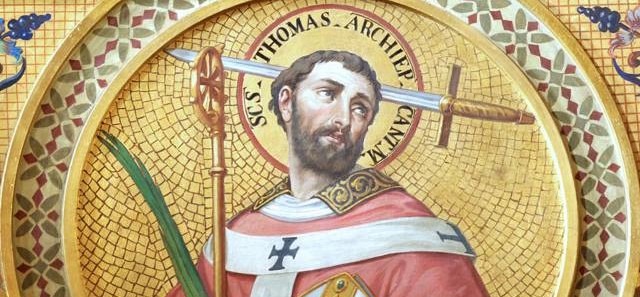

Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Bishop & Martyr

By Joey Belleza

Saint Thomas Becket, or Thomas of Canterbury, is certainly one of the most remarkable saints in the history of the British Isles. As Lord Chancellor to King Henry II, he supported the Crown in its consolidation of power. His candidacy to become Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England was in the beginning part of a ploy by Henry to assert more control over the Church. But the king’s overreach soon went too far, and Thomas, faithful to his oath to protect the liberties of the English Church, stood firm against Henry’s encroachments. This began a protracted conflict between Primate and Prince, which led to Thomas’s seven-year exile in northern France. Only mediators sent by Pope Alexander III allowed Thomas to return to England, but the rivalry between Henry and the archbishop remained strong.

The dispute came to a head when four knights—perhaps acting on Henry’s orders, perhaps not—took it upon themselves to rid His Majesty of his most intractable opponent. On 29 December 1170, they stormed into Canterbury Cathedral as Thomas and the monks began to pray Vespers, with Thomas explicitly telling the monks to leave the doors open to the knights, since “it is not right to make a fortress out of God’s house.” The knights first told the archbishop that he must proceed to attend court at Winchester to account for his opposition to the king. Upon refusing, the knights surged into the choir where Thomas, grasping a pillar that he might not be dragged away from his cathedral, gloriously shed his blood before the altar of God.

In the twentieth century, these events were famously dramatized in T.S. Eliot’s play “Murder in the Cathedral.” In the first act, taking place 2 December 1170, Thomas meets, among others, some knights and four unnamed “tempters.” These tempters—three of whom mirror the three temptations of Christ in the desert—try to convince the archbishop to take safety in the king’s favour, or to take the riches promised if he cease his resistance, or to join a coalition of barons against the king. The fourth tempter, however, urges Thomas to excommunicate the king himself, for, although it would certainly result in his death, the rewards will be even greater:

TEMPTER.

But what is pleasure, kingly rule,

Or rule of men beneath a king,

With craft in corners, stealthy stratagem,

To general grasp of spiritual power?

Man oppressed by sin, since Adam fell—

You hold the keys of heaven and hell.

Power to bind and loose: bind, Thomas, bind,

king and bishop under your heel.

[…]

But think, Thomas, think of glory after death.

When king is dead, there’s another king,

And one more king is another reign.

King is forgotten, when another shall come:

Saint and martyr rule from the tomb.

Think, Thomas, think of enemies dismayed,

Creeping in penance, frightened of a shade;

Think of pilgrims, standing in line

Before the glittering jewelled shrine

From generation to generation

Bending the knee in supplication,

Think of the miracles, by God’s grace,

And think of your enemies, in another place.

Becket, troubled like Christ in the garden, must admit that he has entertained such thoughts about the glories granted to martyrs’ tombs, the miracles attributed to them, and the fate of “persecutors, in tireless torment, / Parched passion, beyond expiation.” But he ultimately rejects all the temptations, especially the fourth.

THOMAS.

Now is my way clear, now is the meaning plain:

Temptation shall not come in this kind again.

The last temptation is the greatest treason:

To do the right deed for the wrong reason.

The natural vigour in the venial sin

Is the way in which our lives begin.

Through the intercession of Saint Thomas of Canterbury, may we not fall prey to that “natural vigour in the venial sin,” that is, “to do the right deed for the wrong reason.” May we remain steadfast in our dedication to Christ and his Church and, if called, to seek martyrdom for no other glory than that of eternal joy in the presence of God.