10 May 2024

The Ascension of the Lord

By Joey Belleza, PhD (Cantab.)

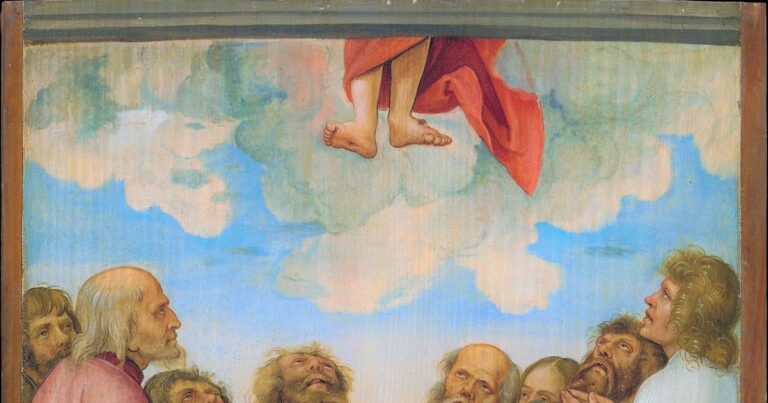

In an essay written before his election as Pope (but published in English in 2006), Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger briefly commented on a certain artistic motif which is often seen in paintings of Christ’s Ascension.

You are surely familiar with all those precious, naïve images in which only the feet of Jesus are visible, sticking out of the cloud, at the heads of the apostles. The cloud, for its part, is a dark circle on the perimeter; on the inside, however, blazing light. It occurs to me that precisely in the apparent naïveté of this representation something very deep comes into view. All we see of Christ in the time of history are his feet and the cloud. His feet—what are they?

We are reminded, first of all, of a peculiar sentence from the Resurrection account in Matthew’s Gospel, where it is said that the women held onto the feet of the Risen Lord and worshipped him. As the Risen One, he towers over earthly proportions. We can still only touch his feet; and we touch them in adoration. Here we could reflect that we come as worshippers, following his trail, close to his footsteps. Praying, we go to him; praying, we touch him, even if in this world, so to speak, always only from below, only from afar, always only on the trail of his earthly steps. At the same time it becomes clear that we do not find the footprints of Christ when we look only below, when we measure only footprints and want to subsume faith in the obvious. The Lord is movement toward above, and only in moving ourselves, in looking up and ascending, do we recognize him.

When we read the Church Fathers something important is added. The correct ascent of man occurs precisely where he learns, in humbly turning toward his neighbour, to bow very deeply, down to his feet, down to the gesture of the washing of feet. It is precisely humility, which can bow low, that carries man upward. This is the dynamic of ascent that the feast of the Ascension wants to teach us.

From “The Ascension: The Beginning of a New Nearness,” in Joseph Ratzinger, Images of Hope: Meditations on Major Feasts (Ignatius Press, 2006).

The future pope’s observations are, as one can expect, spot on. The theme of humility, seen in the washing of the feet at the Last Supper, the anointing of Christ’s feet by Mary Magdalene, and in the thanksgiving of the blind man healed by Christ are certainly operative in the traditional depiction of the Ascension, wherein the Apostles gaze upon the feet of the ascending Lord until he is taken from their sight. In this way, the apostles of the Lord, to include all who follow him, are invited to adopt a posture of humility before him, and in doing so, make his love present on earth even as he ascends bodily to the right hand of the Father. However, the profound insight of the Christian artistic tradition goes even deeper, reaching into the riches of the Old Testament and in doing so illuminating the data of revelation given in the New. To understand this, we must return to the book of Exodus (chs. 19-31), wherein Moses ascends the holy mountain to speak with God and to receive his commandments.

Whenever Moses goes up the mountain, the people must remain in the camp. Only Moses and Aaron, along with Nadab, Abihu, and seventy elders of Israel can accompany him. But these can only ascend partially; Moses alone is allowed to enter the cloud of the divine presence to converse with God. Meanwhile, Aaron and the elders remain at a distance some way up the mountain, where they must wait for Moses to return. Moses, therefore, is the first mediator between God and Israel as a whole, while Aaron and the elders mediate between Moses and the people in the camp.

Following important interpreters such as the Jewish writer Philo of Alexandria and Saint Gregory of Nyssa, the pseudonymous sixth century Greek-Syrian writer known as “Dionysius the Areopagite” reads the ascent of Moses as an allegory for both the ascent of the mystic to God as well as for the structure of the Church. In his brief treatise Mystical Theology, Dionysius interprets Moses as a high priestly character who mediates God’s revelation with the aid of elders or lower priests, who in turn communicate God’s power to the people. The “place” (topos) where the elders stop while Moses continues to ascend is understood by Dionysius, using ideas adapted from Neoplatonic philosophy, as the “place” of God’s powers, where the perfections of created being (such as goodness, unity, and truth) first emanate from God. Dionysius calls this the place “of the presence of that which walks upon the intelligible summits of the most holy places.” Deciphering his densely Platonic language may be difficult for the average reader, but here Dionysius simply means that this “place” where God walks is not identical to God himself, who is higher than any place. This intermediate location between the camp and the summit is also the place of the priests or elders, who form the bridge between Moses and the rest of the nation.

Moses must leave behind Aaron and the elders in this “place” before ascending to the cloud-draped summit of the holy mountain. Christ, as the new Moses, likewise enters into the clouds of heaven on the day of his Ascension, but he leaves behind a new set of elders–the Apostles–who continually mediate his presence to those who remain in the camp of the Church. The Christian artists who depicted the paintings of Christ’s feet at the Ascension certainly understood this ancient interpretive tradition very well. More than mere “precious, naive images,” the paintings of the Apostles looking at Christ’s feet recalls the ascent of Moses up the holy mountain, situating those first followers of Christ in the “place” of Aaron and the elders. They who were at the “place” where the incarnate God walked now continue to mediate God’s presence to us through their successors, who dispense the sacramental ministry of the Church. At the same time, those called to ordained ministry ought to be mindful of their place: they must exemplify the perfections of unity, truth, and goodness which they receive as sacramental emanations from the God above.

The great Solemnity of the Ascension, therefore, is not simply about a single event which closed the earthly mission of Christ. Rather, it points to the new mode of his enduring presence on earth through those who sat at his feet and followed where he trod. It is a key step in the development of the Church, which was already established in its basic form at the Last Supper, and which will be sent forth to all the world through the descent of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. Through the Apostles who humbly remain low at his feet, the revelation first given to Moses and brought to fulfilment in Christ flows down from the mountain of God to the ends of the earth, and accordingly the final words of Christ to the Apostles continue to ring true in his Church: “Behold, I am with you always, even until the end of the age.”