30th March 2024

Between Cross and Resurrection: The Harrowing of Hell,

according to J.R.R. Tolkien

Stefan Kaminski

Easter time seems to get me reflecting on Tolkien’s Catholic imagination. I have previously written about how the dynamic of grace was portrayed in the experiences of the hobbit-protagonists of Tolkien’s Middle Earth sagas.

A key facilitator to this dynamic is, of course, the wizard Gandalf and the various ways in which he plays a Christ-like role, or otherwise serves to at least indicate the Divine action in some way. Gandalf offers spiritual and moral guidance to the hobbits and often speaks for, or of, what we might call Divine Providence. In fact, the word that most aptly captures Gandalf’s role is that of prophet. He speaks the truth: about the individual, about the worldly situation and about the cosmic order.

However, if one bears in mind Tolkien’s aversion to obvious analogy – and which is why too many people miss the foundational role of Catholicism in his writings, or try to undermine it – it is also unsurprising to find that one cannot pin-point a completely Christ-like figure either on Gandalf or any other single character in the Middle-Earth saga. Such a refraction of the roles that Christ fulfils into different characters within the saga is a rather more elegant solution, and decidedly more theologically-eloquent, than mere analogy.

Similarly, the events of Holy Saturday, tied up as they are with the nature of Christ’s kingship, find reflection in The Return of the King, the third book of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Whilst Frodo is approaching Mordor and the final stage of his quest to Mount Doom, Aragorn – the mysterious ranger – is to be found on what is considered by everyone else to be a suicidal mission. He decides to brave the Paths of the Dead, a subterranean mountain path, and home to a lost army of men, now dead, yet trapped by a curse that resulted from their own disobedience long ago. This army, if it can be made to obey, is crucial to countering the extra weight of Mordor’s allies, who are about to throw themselves against the human citadel of Minas Tirith, the seat of the Kingdom of Gondor.

The nub of the question, of course, is that of authority over this terrifying army. No living man could pass through and survive: the dead do not obey the living. Only one exception exists; and this takes us back to the origin of these men’s story. The curse that this army brought upon themselves was a result of their breaking oath to aid the Kingdom of Gondor against the forces of evil. That oath was made to the King of Gondor, and as such, the only person with the authority to command its bond and release from the curse is the self-same King – or, of course, a legitimate descendant who can wield that authority on his behalf.

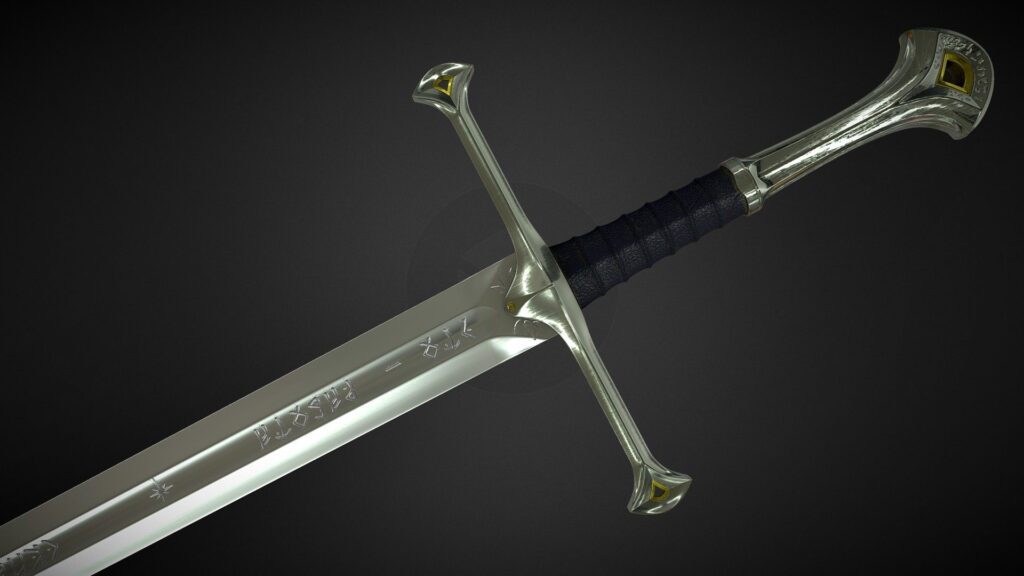

By this point, Aragorn, is of course known to the avid reader to be the heir to Elendil, the first King of Gondor. And so, the trepidation with which we accompany him along the Paths of the Dead, as the dreadful and invisible army gathers around him, is offset by the hopeful expectation of something dramatic. And we are not disappointed. The dead king cynically strikes out at Aragorn with his sword, only to find it halted in its path by Aragorn’s own blade: something that no mortal would be able to effect, other than one who bears that original authority.

Recognition of the King who stands before them rustles through the horde; their assistance is secured; and when they finally fulfil their oath in the present conflict, they disappear with a whispering sigh of relief, finally free to rest.

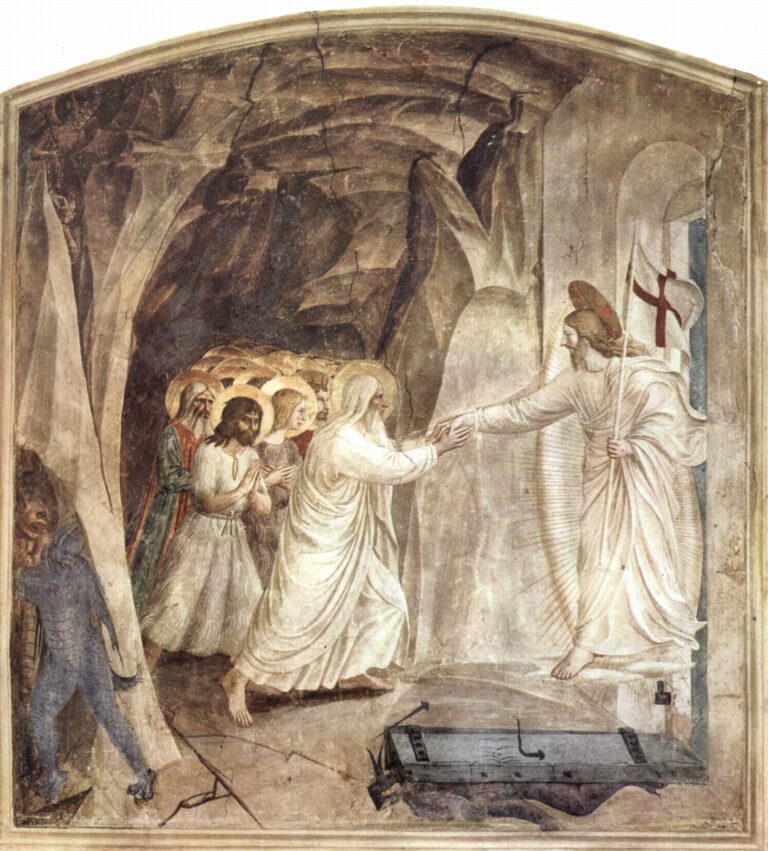

It would be hard to find a more dramatic visual aid to explaining Jesus’s harrowing of hell on Holy Saturday, especially for an audience of teenagers or young adults. For those puzzling over the words in the Apostles’ Creed, “he descended into hell”, Tolkien provides a vivid point of reference. The imagery poignantly evokes and gives life to St Paul’s reference to Christ as the “Lord both of the dead and of the living” (Romans 14:9). In turn, the logic of Christ’s command over the dead is helpfully drawn out by Tolkien’s narrative.

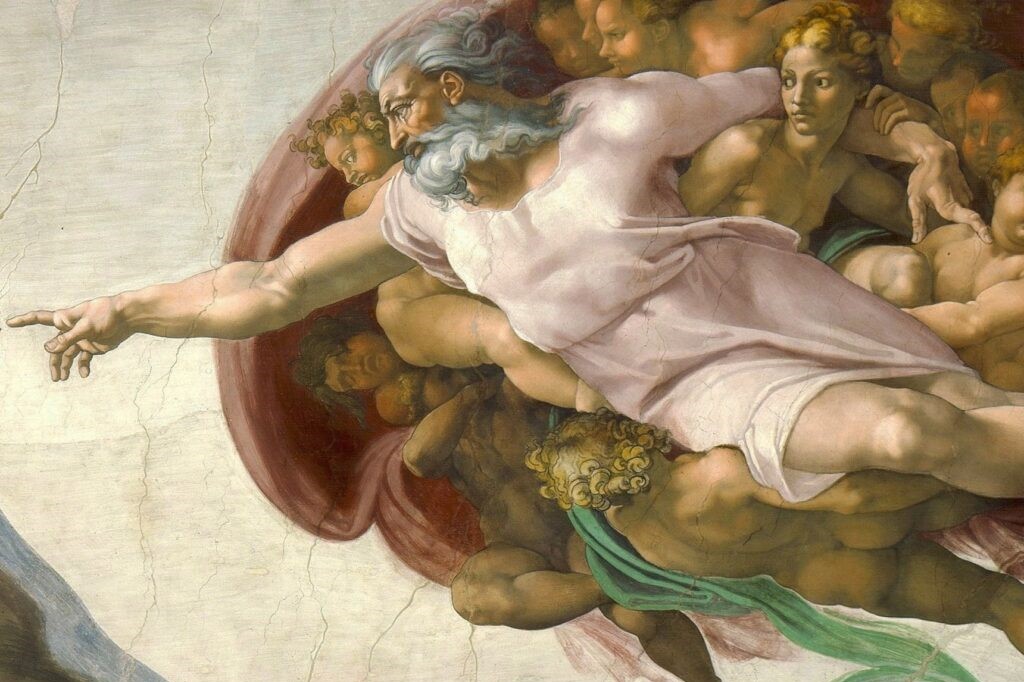

As with our army, the key to Holy Saturday is in the origins, and can be summed up in the words: paradise lost, paradise regained. Our first parents suffered the loss of Eden, ‘paradise on earth’, through breaking the primal covenant that governed their relationship with the Creator. Having said that, this consequence can be – indeed should be and is – considered in view of the greater blessing that results: namely the promise of a renewed and glorified life at the end of this time. Thus, the Exsultet, the Easter proclamation that is sung before the newly-lit Easter candle at the Vigil, pronounces the words, “O happy fault, O necessary sin of Adam, which gained for us so great a Redeemer!”

The loss of Eden resulted in the entry of death into the world (cf. Romans 5:12), with the ensuing mortality of the human race. Again, whilst we might naturally consider this a curse, in the schema of God’s providence it rather turns into a blessing if we consider that God did not wish for fallen humanity to continue an immortal existence alongside the effects of evil. Thus, the necessary end of our fallen mortal nature with our bodily death results in a state of waiting, a state of the soul’s existence apart from its body.

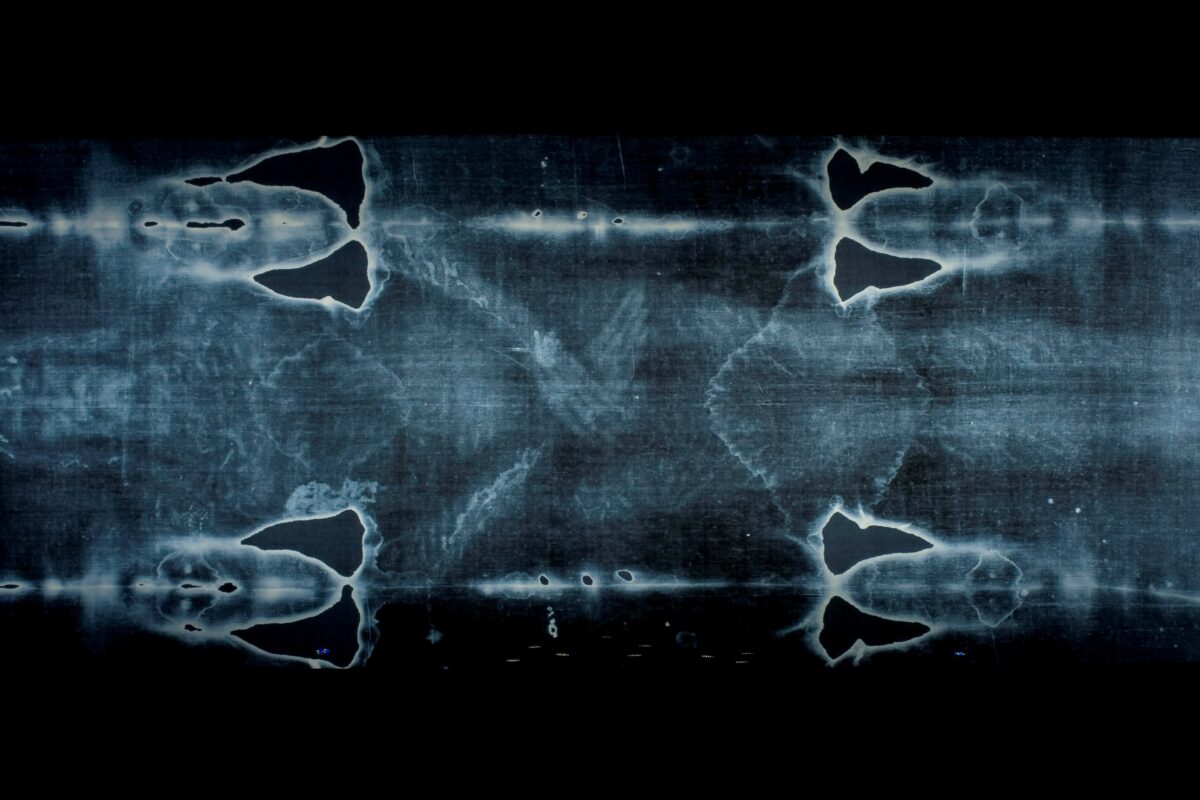

The greatness of the mystery of God’s love, which we saw executed in the bloodiest manner in yesterday’s Solemnity, is of course that it goes beyond that disobedience and rupture instigated by our progenitors and continued throughout history. It wishes to encompass every person, in harmony with their own volition. However, until the price of that disobedience was paid, those who had already died remained ‘trapped’, awaiting their liberation. Their souls, whilst free of their mortal body, remained – according to justice – outside the presence of God. The dead were bound by the original curse, awaiting the fulfilment of the bond of justice.

Unlike Aragorn’s army, who have to fulfil their original oath and fight, the price of humanity’s ‘oath-breaking’ is paid freely, “not with silver or gold, but with the precious blood of Christ” (1 Peter 1:18-19). Thus, Christ’s death effected two things: firstly, a universally- and eternally-valid sacrifice for any and all human sin, including those who had come before him; secondly, his ‘entry’ into the realm of the dead via his mortal body, yet wielding the divine authority of the king to whom those souls were originally bound.

Only the Son of God, He through whom “all things were made… and without [whom] was not anything made that was made” (John 1:3), could enter the realm of the dead and command its bond. Only the rightful King could wield authority over every soul, whether in the province of the dead or the living. Only the Cross of the incarnate God could break the brass gates and shatter the iron bars of hell asunder, as is recounted by two of the men risen from the dead in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus.

No surprise, then, the prophetic words of Hosea, “O Death, I will be thy plague; O Sheol, I will be your destruction”.

Or the words of St John Chrysostom on Easter night: “Hades is angered… because it has been mocked… destroyed… it is now captive.”

Or the ancient hymn for Easter Matins: “Today Hades tearfully sighs: ‘Would that I had not received Him who was born of Mary, for He came to me and destroyed my power.’”

The harrowing of hell – and what a harrowing! – is unsurprisingly an intrinsic part of the logic of the Easter mystery. Viewed inseparably from the death and resurrection of the Lord, it is witnessed to by the Apostles themselves, and traced from the very earliest Christian traditions.

It is appropriate that Holy Saturday should retain a sense of stillness and quiet preparation in the earthly life of the Church: momentous events are taking place in the spiritual realm, before the glory of the Lord bursts forth from the realms of the dead, with the saving banner of the victorious Lamb leading the mighty hosts of heaven.